This month we are starting a new feature with the first installment of the serialized novelization of “Lunatics!” by Rosalyn Hunter. We’re also addressing a lot of behind-the-scenes problems with workflow, asset management, version control, and project management problems. In fact, we’re considering doing some software development to help our project (and other free-film projects).

Lunatics!

Chapter 1 — Leaving Earth

Little Georgiana Lerner dug her hands deep into the rich black soil. The setting sun cast shadows through her auburn hair as she crawled underneath the oak tree turning to look up at the sunlight shining through the dark green leaves.

Georgiana loved being in her garden. She had planted pumpkins last year, and this spring she had grown lettuce, radishes, and marigolds. The lettuce and the radishes were gone, eaten in salads with dinner, but the marigold leaves tickled her feet as she rolled among them, leaves sticking in her hair. It was warm now, but after sunset the night would turn chill so she had come early instead of sneaking out after dark as she had originally planned. She sat up and dug in the earth with her hands uncovering a pink earthworm.

She threaded her fingers through the dirt, lifting the soil to her nose and then dropping it to fall in clumps back down to the ground. Georgiana loved the smell of the earth. She wondered what would happen to the garden when she left. Would someone else take care of it, or would it grow wild sprouting up the odd radish or pumpkin every other year? No matter what happened, she would never come here again.

They would be leaving in the morning. Daddy was already setting up house. She had said goodbye to Daisybell and Katz the goats, and the big old dog Brownie. She would miss Brownie the most even though he wasn’t her dog. She knew that he would be sure to see her off when she left tomorrow morning.

She lay down and tried to hug the ground but all that she succeeded in doing was to tickle her ear on a blade of grass, staring at the earthworm who shimmied forward trying to dig his way back into the dirt. She lay there for a long time, watching the leaves moving in the wind. She lay still as an ant crawled across the back of her hand. Then she turned over and stared at a magnificent landscape of clouds turning pink and orange in the pale blue sky. “Orange like my marigolds,” she thought.

The moon had risen. It shone a pale white bathed in blue. “I wonder,” she thought, “if I had a big enough telescope, could I see Daddy there?” She was considering climbing the tree, when a beep on her belt alerted her that her mother was calling. She pushed the blue crystal switch and heard her mother say, “Georgy, dinner is ready.”

“Be right there Mama,” she said standing up and dusting the leaves and grass off of her clothes with her dirt-covered hands. It only succeeded in getting them dirtier.

She looked up. “Maybe right now, Daddy is looking down at me in my garden. Then he’d be watching me, just as I’m watching him? It’s almost like we’re together, and in just a little while,” she said, “I’ll be on the Moon too.”

Chapter 2 coming in December!

All About Workflow

What We Need

In all honesty, our project is struggling right now. We’re running into some of the limitations of Blender as a 3D animation package. Blender is a fantastic program, but it was not really designed with long-term, complex, many-file projects like ours. Doing this project really stretches its capabilities.

The problem is not with modeling, rigging, or animation per se, but rather with the complexity of maintaining a long, ongoing animation project. We thought we’d definitely run into this at some point, but we’re finding it to be an issue even now, in producing just the first part of our pilot episode. So it’s time we started addressing these problems of workflow, collaboration, and asset management head-on.

FAULT TOLERANCE

We did not put human beings on the Moon and return them safely to the Earth by not making mistakes.

Mistakes are an integral part of every human endeavor. The bigger the endeavor, the bigger the risk, and thus the bigger opportunities there are for mistakes to be made.

What distinguishes the system that gets to the Moon from the one that doesn’t is how it responds to mistakes. Systems engineers call this “fault tolerance”.

There are different approaches to fault tolerance:

- Soft failure — Something goes wrong, it doesn’t get fixed, but it doesn’t end the mission. In other words, small errors have small impact

- Redundancy — Probably the best known factor in space flight: build two (or even three) systems, each capable of handling the whole mission. If system A fails, then switch to system B. If that fails, switch to system C (and hope that doesn’t fail!).

- Repairability — Allow the crew to fix the problem during the mission. Send tools along to fix things when they break.

- Simplicity — Reduce the number of things that can go wrong by reducing the number of elements you are relying on. Also known as “too dumb to fail”.

Any successful complex system — including your own body — illustrates all of these principles at work (e.g. this is why you are made of cells).

When a system lacks fault tolerance, we can say that it is “brittle”.

Our first problem with Blender is that it is still too brittle. Tiny mistakes in certain parts of the workflow can result in catastrophic failures — especially if they are not caught right away, and this is exacerbated by the fact that errors are not always clearly visible to the user.

Highly expert users can learn to step around the faults of a brittle system. This is the main reason that it is such a terrible idea to test your own software code. Being the author, knowing how you planned the software to be used, means you will subconsciously avoid the dangerous moves that will trigger buggy unpredictable behavior in your software. But give it to a clueless user for only a few minutes, and they’ll typically discover a fault the hard way.

With Blender, a less experienced user will try things that experts have trained themselves not to attempt. And in so doing, they’ll trigger some bad behavior.

LINK FAILURE!

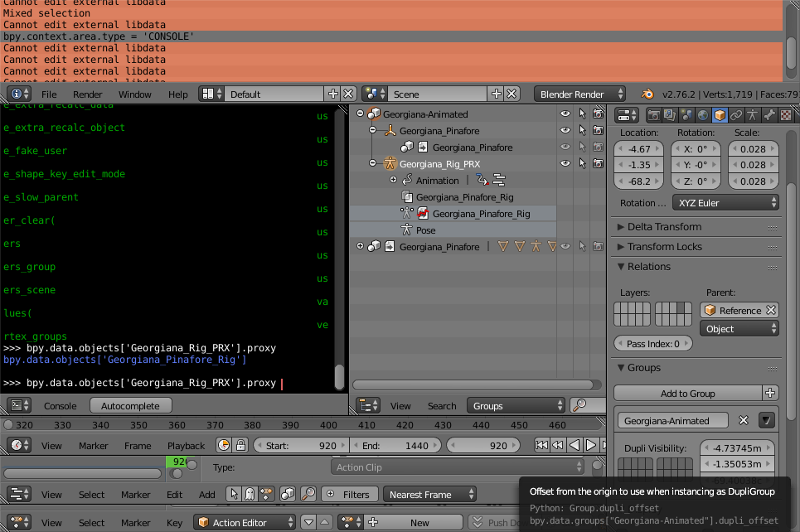

My #1 pet peeve with Blender is the way it can silently lose linked objects…

Broken library links in Blender.

This is a particularly nasty failure mode, because it loses data permanently and it can do so without giving the user any overt warning. If you only ever work on your own files, this might not seem so terrible, because you’ll typically recognize when something is missing. But for teams (or for using files you created too long ago to remember them well), the lack of any obvious warnings means you can easily overlook lost library links. And once you save the file again (with whatever new edits you’ve made), the links are gone forever.

Now, of course, you should save often and update the project repository with the saved data. And if you did this, then the last version from before the error will have the links. If you immediately notice the problem, then, this presents only a little trouble to go back to the earlier version.

But the real kicker is when you don’t notice. Maybe you aren’t working on the affected part of the scene (e.g. perhaps you are updating the textures on the walls or background set dressing while the problem occurred in character animation).

In that case, the file can lose data, then you put a lot of work into the file. Now, if we go back to get the lost data, we’ll lose all the work you’ve done since then. There is no “diff” utility for Blender files to tell us what exactly you changed, and no “patch” utility to apply those changes. So as a result, we can’t simply merge your changes back into the corrected file — not in any automated, repeatable way.

Instead, an expert user will have to go through; manually find the changes; and apply them to the file. This is tricky and error prone. It can be almost as much work as just repeating the lost work, and it typically requires a more skilled user than the one who made the error (certainly no less so).

That’s lost time on a project. And if the project is complex enough, this kind of incident will be inevitable. We’ll just have to include this kind of clean-up time as part of our predictions on production schedules.

This poor library-linking behavior strongly discourages teams from using linked assets on a project, which is a real problem for two reasons:

- Separation of Concerns – Without linking, it’s hard to separate different parts of the project so that two users don’t have to edit the same file to work on a scene together.

- Consistency and Continuity – We want updates to scene elements to propagate through to our finished scenes. But if we are working with copies rather than links, we have to propagate those changes manually. It’s very easy to overlook that!

LINK REPAIR!

Fortunately, the work Bastien Montagne has been doing on the Blender Asset Management Project is already addressing some of these problems. Using the very latest development build of Blender 2.76 from blender.org (I tested with Build #4b316e7 for Linux), it is already possible to deal much better with this problem. Instead of simply dropping lost links, this version of Blender creates a “broken link” object, which allows you to edit the link path in order to fix the link.

If everyone on the project were using builds of Blender with this feature, it would greatly reduce the risk of accidental data loss.

It is far from perfect, however. There are still some kinds of breakage which aren’t easy to fix this way. For example, some of our early shots were created with earlier versions of the character files. During subsequent character development work, we decided the names used for armatures were obtuse and inconsistent, and so we refactored these to a more systematic and mnemonic naming scheme. Unfortunately, this broke links for any animation file using the old names. Even with Montagne’s upgraded version of Blender, it does not appear to be possible to fix this kind of error (The file is looking for a proxy object within a linked group — but the name it is using is now incorrect. I’d really like to be able to just type in the new name, but that doesn’t appear to work!).

The need to repair damaged files also calls for better tools for analyzing the differences between Blender files and applying updates in an automated way — these are additional use cases for “diff” and “patch” utilities for Blender, which we will come back to in the DAMS/VCS section.

IMPROVED REPEATABILITY

Another problem that confounds our workflow is the difficulty of automating certain steps in production. We often need to use different layer settings for editing and revising assets, but then have to make sure those get set back to the correct values for rendering (it used to be possible to do this by keyframing the layer-visibility settings, but this feature was removed without explanation). We need to be able to make low-quality “guide renders” of different kinds to check lighting, shaders, animation, and so on. But then we need to produce the correct final renders.

Sometimes we’d like to have more than one version of a scene — two different camera angles for one animated sequence, for example. We’d like to be able to set this up in a routine way, and not have to worry about these problems when rendering. In fact, we’d like rendering to happen automatically on a dedicated render-cluster so it doesn’t have to be constantly watched and corrected.

Even in the modeling phase, we have repeatability issues — for example, it is very tedious to make sure that our character armatures are all identical, so that animation can be copied from one character to another (an important reuse goal to keep our project feasible.

A “build system” (or “render management system”) would be very useful, but we do have some conflicting demands to work out. For example, we’d like to keep our “source code” small, but we’d also like to retain intermediate steps which are very compute-intensive, since it can take days or even weeks to render our scenes on typical single-desktop computers. Those final renders can be very large files (or very large collections of files, since the final renders are individual frames, represented as PNG or EXR files).

I’m not sure that these things can be solved in an integrated way. We might need something more like a toolkit with lots of scripts to help us deal with these problems.

Version Control & Asset Management

DIFF, PATCH, & MERGE

Version control for Blender files is stuck in the Dark Ages of 1970s-style “lock based” version control. This means that each file can only be edited by one person at a time. In order to enforce this, we have to enforce “locking” of files to prevent the accidental case of two users editing the same file at the same time.

Since Blender severely discourages us from using a lot of linking to external files, this is especially awkward. And it’s a problem even if the items being edited are clearly separated within the file. So, for example, we can’t have one person working on set dressing, another working on materials, a third refining the character models, and a fourth animating character sequences. But these really should be separable elements.

For software, this problem was solved in the early 1980s with the release of the “Revision Control System” (RCS) which was the first “merge-based” version control software. This took advantage of “diff” (“difference”) and “patch” algorithms that work on “list-structured” data like lines of text in a program source file. It could take one edit from one person and another from another and apply both of them to the same originating file to create a combined result, which included the updates from both.

This was refined in successive version control systems — “CVS”, “Subversion”, “Mercurial”, “Bazaar”, “Git”, and so on.

But to this day, we do not have routine automated merging tools for “graph-structured” data like Blender files (nor for Inkscape, Gimp, Audacity, or most other multimedia authoring formats).

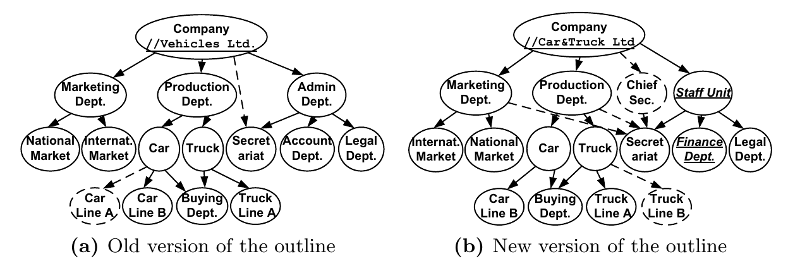

The need for “diff” and “patch” operators for Blender files.

A little investigation into the computer science literature shows some reasons why this might be. The general problem of matching changes in a graph structure is a hard problem in computer science — to be precise, it’s called an “NP-complete” problem. This means there is no general closed-form solution for it. It does not, however, mean that it is completely insoluble. It just means that you need a “heuristic” approach, and have to accept that it might not always be resolved.

In fact, though, that’s true of the text-matching problem in practice, so it’s not really a show stopper. Good algorithms are hard to find, but we were able to find a 2006 paper by Johann Eder and Karl Wiggisser which appears to fit our needs very well. Their data was actually quite a bit less well-behaved than we expect ours to be, and so there’s good reason to expect their algorithm will work even better on graphs describing Blender files.

In particular, we have a very good “similarity” function which means that misidentifying transformed nodes will be rare. This is largely because our nodes have “types”: you will never see a “Texture” mode get changed into a “Mesh” node! Such a change would be nonsense with a Blender file. So this greatly reduces the range for confusion for us.

Without going into technical detail, the algorithm in the paper tries to find matches between nodes existing in the original and edited structures using intrinsic features (such as the names of the nodes) and structural features (such as common “parent” or “child” nodes). It then generates an edit script for convertng from original to edited, which gives us our “diff” structure.

A DAG Comparison Algorithm and Its Application to Temporal Data Warehousing

Johann Eder1 and Karl Wiggisser2

Abstract.

Abstract. We present a new technique for discovering and representing structural changes between two versions of a directed acyclic graph (DAG). Motivated by the necessity of change detection in temporal data warehouses and inspired by a well known tree comparison algorithm, we developed a heuristic method to calculate an edit script transforming an old version of a graph to the new one. This edit script is composed of operations for inserting and deleting nodes and changing labels and values of nodes as well as for inserting and deleting edges to cover rearrangements of nodes (moves). We present the prerequisites of our approach, the different phases of the algorithm and discuss some evaluation results gained from a prototypic implementation. Our approach is applicable to arbitrary labeled DAGs in any context, but optimized for rooted, ordered and labeled acyclic digraphs with a small rate of changes between the DAGs to be compared.

Abstract for Eder & Wiggisser’s 2006 paper on

comparing related graph-structured data

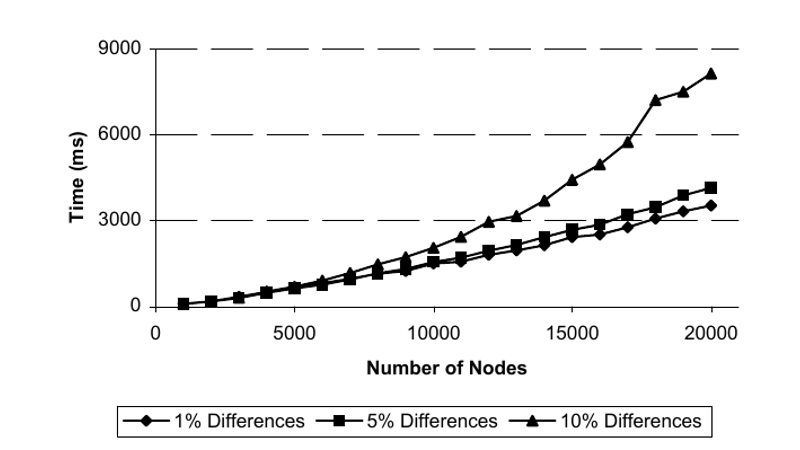

Algorithm performance on simulated data (Eder & Wiggisser 2006, Fig. 5b). Note that even for graphs with 20,000 nodes and a 10% change in structure, the algorithm is able to resolve the changes in just a few seconds. This is a much tougher problem than a typical Blend-file merge will be.

Algorithm performance on simulated data (Eder & Wiggisser 2006, Fig. 5b). Note that even for graphs with 20,000 nodes and a 10% change in structure, the algorithm is able to resolve the changes in just a few seconds. This is a much tougher problem than a typical Blend-file merge will be.

1

University of Vienna, Dep. of Knowledge and Business Engineering

(johann.eder@univie.ac.at)

2

Alps Adria University Klagenfurt, Dep. of Informatics-Systems

(wiggisser@isys.uni-klu.ac.at)

Abstract and some results froom Eder & Wiggisser’s 2006 paper on comparing related graph-structured data. Full citation:

“A DAG Comparison Algorithm and Its Application to Temporal Data Warehousing” Johann Eder and Karl Wiggisser.

DOI: 10.1007/11908883_27 · Source: DBLP.

Conference: Advances in Conceptual Modeling – Theory and Practice, ER 2006 Workshops BP-UML, CoMoGIS, COSS, ECDM, OIS, QoIS, SemWAT, Tucson, AZ, USA, November 6-9, 2006, Proceedings.

MERGE-BASED VERSION-CONTROL

It’ll take a bit of additional work to create the equivalent to the “diff3” utility which works with the original and two different edited versions, and it will require an additional layer of code to get Blender files into and out of the directed acyclic graph representation needed by the algorithm, but these are relatively straightforward implementation problems. The biggest problem is researching the limited documentation available for the Blender file manipulation packages — that may require a code review. The need to map named links to ordered links or to an expanded graph model will also take some design and coding work. Fortunately, the documentation for the Blender “bpy” library, needed to implement the patching operations on real Blender files is pretty solid.

Once we do have “diff” and “patch” operators that work on Blender files, though, we will be able to interface these into existing version control packages to get much more usable VCS for collaborative work on Blender animation projects. Furthermore, the same tools should work for other types of authoring data, with appropriate adaptation code. This could be a huge leap forward for artistic collaboration over the Internet.

A quick survey of available version control system software suggests that our best candidate for a pluggable VCS that would allow us to deal with heterogeneous data types and merge algorithms would be “Bazaar”. This package has an excellent and well-documented API for adding such features. The only downside is that Bazaar has essentially lost entirely against Git in the market for software VCS.

One advantage of this, though, is that, having already lost the battle for dominance with software, Bazaar might find a new life as a VCS for multimedia projects, if we can extend it appropriately. This seems like the ideal outcome for us.

Alternatively, if there is simply not enough interest to bring Bazaar’s code back into regular maintenance, we could adapt to Git, Subversion, or Mercurial instead. This seems to be technically harder, but probably not completely unfeasible.

LINKING DIGITAL ASSET MANAGEMENT & VERSION CONTROL SYSTEMS (DAMS+VCS)

Digital Asset Management Systems (DAMS) are primarily about finding digital assets (or “resources”) when you need them. We are currently using Resource Space for this. Resource Space is a LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP) application for doing this. This deviates from my usual bias towards Python-based applications which I am better able to hack or contribute to. However, it is a very nicely-polished web application, and not that hard to connect to. And I had a not-so-good experience with Plone, simply due to the lack of maintenance.

The biggest flaw with using Resource Space as it is is the lack of any integration with our version-control system. There are some possibilities for improvment, though. Using add-on packages, it may be possible to convert Resource Space to use file-based storage which coincides with a “local copy” or “snapshot” of the project files in the VCS. Another possibility is to use a pluggable web-based API with Resource Space to automate access to it from scripts.

These would only provide a read-only connection to the VCS, which might be acceptable, but it would also be nice to have VCS features visible directly in the resource page (such as being able to change what version you are accessing). This probably requires some modification to Resource Space itself — or possibly creating a new add-on package for it.

DEPENDENCY-TRACKING

A special problem for multimedia projects is their size. An animation project like ours runs into multiple gigabytes of data in the VCS very quickly. This makes the standard software development solution — just checkout an entire copy whenever you want — very awkward.

Instead, it is much nicer to just be able to pull the files you need out to work on, and then re-upload any changes you make to them.

To do this safely, we need to be able to tell what library files we need to get when pulling a Blender file out to work on.

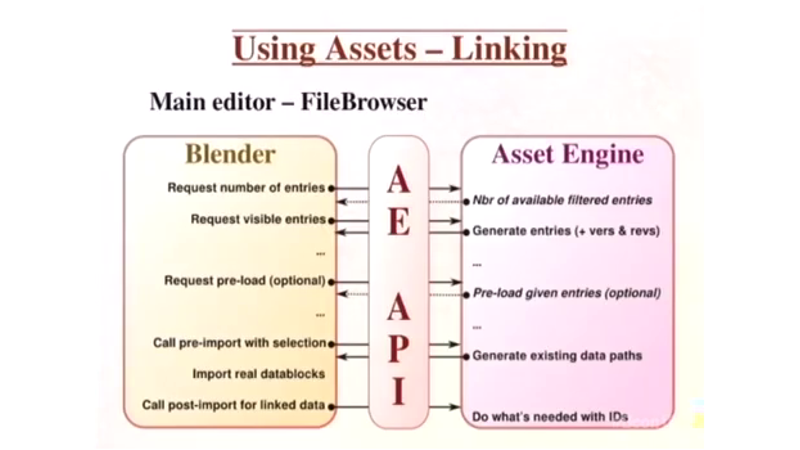

Fortunately, this dovetails nicely with the direction of the Blender Foundation’s asset management project, as explained by Bastien Montagne in his 2015 Blender Conference talk, “Blender & Asset Management”:

Bastien Montagne’s full talk at the 2015 Blender Conference (about 25 minutes)

The great thing about Montagne’s approach is that by creating an “Asset Engine API”, with minimal modifications to Blender, he’s proposing a very attainable goal inside the main Blender development project, and simultaneously opening the field up to competing server backends for asset management. This is really good, because we’re all using different software for this, and I don’t think any of us really wants to change. On “Lunatics!”, we are using Resource Space as a DAMS, largely because it works well as a public-face for these resources online. Integrating it with Blender should be a relatively simple problem of bridging between the AE API and one of the pluggable Resource Space through-the-web APIs (alternatively, we could integrate directly with our VCS).

If all it has to do is to fetch resources after Blender determines the dependencies, this should be quite simple. The biggest block for this right now is that the API may not be fully implemented in Blender and it certainly isn’t well-documented yet. I would love to work with Montagne and Blender Foundation on providing this secondary back end for the AE API.

Otherwise, just getting the API documentation published would be awfully helpful to us. It’s apparently just a half-dozen or so JSON remote procedure calls, so it should be pretty simple to document.

FEASIBILITY STUDY

Coming up with requirements is one thing. Building a solution is another.

We’re going to have to accept that, given very limited resources, whatever solution we come up with is going to have to tread lightly on development, leveraging existing software projects as much as possible. It’s even possible that full solutions already exist, and I just haven’t found them yet. But even where they do not, we will probably be simply bridging between different components from other sources, most of the time.

There is quite a bit of software out there to start with. Asset management

packages for Blender have gone through several false-starts, leaving us with

an odd assortment of poorly-documented codebases to research for starting points. Clearly this is going to take some time to study.

I hope to publish results of a deeper review of adaptable code in a later article (possibly January or February — it depends on how long the research takes). Some of the things I’m going to look at next:

- Blender-Aid: Defunct Blender file repair and refactoring tool written in 2009, abandoned by 2012

- Amber: Asset management tool being created as part of the Gooseberry project, which may be using a substantial amount of Blender-Aid code

- Bazaar: Python-based distributed VCS software package with excellent API documentation and pluggable differencing and patching engine

- Resource Space Add-Ons: Including a pluggable remote API, filesystem-based resource storage which might be compatible with VCS, and modifications to support VCS semantics in the web-based user interface (e.g. controlling which version is retrieved)

- RenderChan: Build tool for automating animation production, developed by Konstantin Dmitriev for Morevna Project

- Peragro: Previously called “DAMN” for “Digital Assets Managed Neatly”, this is an engine associated with the Open Game Art project, which provides the ability to index objects within Blend files (rather than just the files themselves).

My plan is to review the available documentation and possibly even source code for these packages, with the idea of integrating them into our DAMS/VCS/Workflow system or using them as a basis for writing new application software. I’m also considering whether it’s worth creating a larger umbrella project for maintaining or at least documenting these tools, but I fear engaging in a Waste Of Money Brains And Time, when I am already over-committed.

Other News

- Interns

- Travis Souza and Keneisha Perry will be finishing up their semester internships this month. Travis has been working mainly on set assets for the colony set to be shown in Part 3 of our pilot. Keneisha has been working on character development and most recently on primary character animation, completing the train sequence at the beginning of Part 1 and the Press Conference scene. There’s only a few more character-intensive scenes to animate in Part 1, which will leave us mostly with mechanical animation work to do.

- Schedule

- With the holidays so close, I’m starting to think we won’t have a release before the end of the year, which is frustrating, but we really are a lot closer to being finished. I wouldn’t completely rule it out, although the rendering time alone may push us over, even if we can finish the animation.

Until Next Time!