A reflection on generative art, AI, automation, personal ritual, and process in making art in a social context. Wandering with only a bit of structure, because this is a mental and philosophical journey that ties into a lot of other things I have struggled to articulate about what I’m doing with this project, and why I feel I must do it.

What Can the AI Beast Do For Me?

In 2022, I spent some time experimenting with MidJourney, which is either based on, or very similar to “Stable Diffusion” which is an open source tool for generating imagery from textual prompts. This is a pretty amazing technology! I spent a lot of time experimenting with it, and it was a lot of fun. I posted many of my experimental results here on my Production Log in July, August, and September of 2022.

But is it really useful? And if it is, do I really want to use it?

Backgrounds

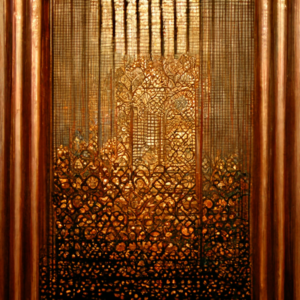

Detail in the background, where complexity looks good, but specific details are unimportant.

Surface textures

LIkewise, I could use textures generated by AI to decorate wall panels, where I want a certain feel, but don’t need specifics.

|

|

|

Screens Images

Finally, it’s great for generating sketchy screen displays for monitors in a shot where I don’t really need you to see any specific details.

|

|

|

|

Note that an IDEAL application of this workflow would have been to create the “Mission Control” set in episode one of “Lunatics!” I did not do that, partly because I made that set well before this technology came our.

I did also demonstrate using these materials to make a 3D prop:

This is definitely a possible workflow, and I generally am interested in automated techniques that will speed up my work.

But note how I used the word “specific” in each of the three cases above. By using these techniques, I necessarily lose some control. Also, the machine doesn’t necessarily “think” the way a human does. I realized in my experiments with MidJourney that what I often wanted to do was to juxtapose contrasting elements to create a dramatic effect. And MidJourney really didn’t like that. Unless the resulting image was a cliche — something that would already be in its training set, then it was very hard to get it to do what I wanted.

The indigo jungle above is at sunset. That isn’t solely because I chose that — I tried different conditions, but it’s only at sunset that a *terrestrial* jungle, with green vegetation, might appear indigo. So it’s really the only time MidJourney wanted to draw that. I compromised (just a little) by letting the machine have its way.

I found that one way to sort of get what I wanted was to generate elements separately, and then combine them in a conventional art program, like Gimp. I did a video “log extract” on this workflow, too:

Even here, I found the generator would fight me a bit. The alien creature it generated was barely plausible as a life form, and certainly didn’t show much logical structure. It also might generate a “planet” in the sky, but did not really like making it round — which is pretty much the most consistent thing about planets!

This is all easy to understand, knowing how the software works — or how it doesn’t. It doesn’t work by understanding the prompt, or the 3D reality that it is representing. It’s basically just trying to follow in 2D compositions that it has “seen”.

This becomes apparent even in really basic ways, like framing a portrait. MidJourney has definite ideas about how much of the body should appear in a portrait and what aspect ratio it should have. If you push this a little bit, it kind of rebels:

|

|

|

Various attempts to generate portraits of women at an unusual aspect ratio. Only one succeeded (upper right). The others did bizarre things with the prompt, generating oddly deformed, stretched, or doubled images. Clearly the usual aspect ratio and fraction of the figure shown are part of the model’s training on what constitutes a “portrait” (i.e. not merely that it is a picture of a person).

Note that what it is objecting to is simply the taller aspect ratio specified for the image. I wanted more of the body. In these, it basically only “succeeded” once, with the image on the upper right. For the others, it rebels by generating weirdly stretched, doubled, or hybrid images. This is such a trivial issue that it really strikes me that even subtle design changes will destabilize results.

Also, it did not present racially/ethnically diverse people on its own. If you ask it for a “woman”, it invariably produced a white, Western European or American woman. I would have to be specific about race, ethnicity, and/or nationality. And there is a sort of “cross talk”, because the software doesn’t really understand grammar: note how the “American woman” in the lower right is wearing a bandana that resembles a US flag. It’s a bit on-the-nose, isn’t it?

Of course, I am not a good portrait artist. It would not be easy for me to render faces at the general quality level of these portraits. But at least I would know that people don’t have heads growing out of their other heads. And I don’t know how I feel about that drab green it likes so much.

In general, I think I would rather try to find a more talented portrait artist if I needed this kind of art, or just accept my poorer skills as a portrait artist. Largely because the text prompt is such a clumsy way to communicate what I want visually.

Indeed, I often find that I would rather make a sketch than try to explain what I’m looking for, even to a commissioned human artist. The visual communication is just easier than trying to figure out increasingly elaborate ways to describe spatial relationships — especially when what I want is not the “cliche shelf” answer (i.e. something the model has “seen” in its training set).

Now, of course, I’m aware that these experiments were three years ago, and AI users have worked out more sophisticated ways to constrain the models to get closer to what they want. But it is certainly not a simple and intuitive process. This AI generation approach involves a substantial amount of commitment, practice, and effort. And yet, it still jerks the wheel away from you and tries to go its own way.

This is particularly clear to me as a science-fiction artist. What I want is often not going to be in the training set of expected results. I went further afield to try to create some alien creatures, and the results are ultimately pretty disappointing:

I tried this because it approximated a drawing I had made many years ago for a science fiction project of mine.

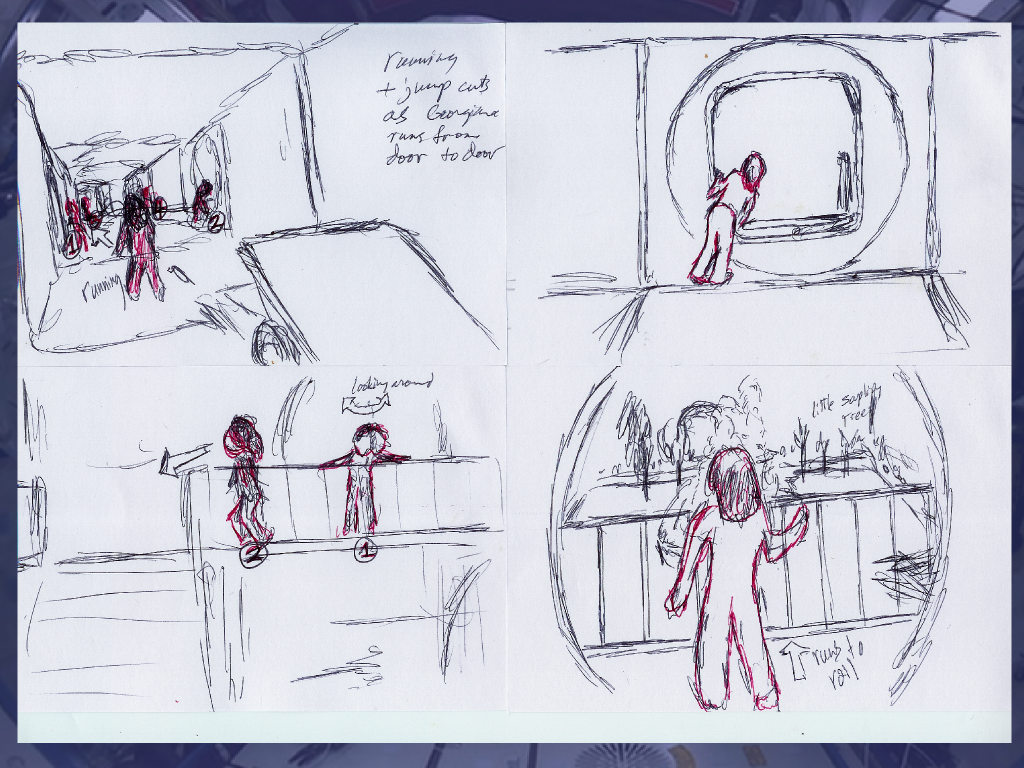

I was reminded a little bit of a problem I encountered early on Lunatics, when I was creating storyboards. I figured that I could save some time by just using photographs of Soyuz launch operations to storyboard some of the shots in the launch scene of “No Children in Space”, but I often couldn’t find quite the angle I wanted.

So I’d find the nearest thing and use that. But it nagged at me. The point of a storyboard is to show the shot you want — not the sort of similar shot someone got with a camera once and put up on Flickr.

My hand-drawn storyboards are no great works of art, but they do show the composition that I wanted — which was the point!

If a generative AI program is going to give me the same problems I had with stock images and clipart, then what is it buying me, really?

And for background art in a project like Lunatics, there is a lot of fun in sticking in “easter eggs”, like all the posters in the train station, many of which are from other open movie projects, and one is a subtle reference to a popular SF franchise you might have seen:

The arrival/departure screen also includes a few subtle SF easter eggs. I could have generated poster images with AI that would read plausibly as posters from a train station, but where would the fun be in that?

What a minute…fun? Yeah. This isn’t really “work”, is it..?

These projects are creative expressions. I’m not merely producing content to be consumed. I’m trying to say something to other human beings through an expression of my own humanity.

And part of the purpose and experience of art is in the making of it, not just the final product. Remember Jackson Pollock and “action painting”? The whole idea there was that the art lies not only in the finished product, but in the process of creating it — an experience for the artist or even a performance in front of others. The product is more a record of that process than it is the objective.

|

|

Similarly, if I consider what I’m doing with “Lunatics!” it is clearly not solely about the end product? The reality, invisible in the finished product, that it was made by a free culture collective using free software authoring tools, is fundamental to its meaning as a work of art (or as labor). It’s not being made “by any means necessary” to meet some commercial objective. Not even if we are hoping to monetize it.

Action paintings make it the whole point, but the meaning of all artworks is reflective of their context. People don’t just like the “Mona Lisa” because it’s a pretty painting (honestly, I have seen paintings I liked better), but because it feels like it has a story behind it, and we’re intrigued by the life of Leonardo da Vinci, who made it.

Logs and Ritual

Likewise, in producing “Lunatics!” I have created far more output in the form of screencasts, logs, tutorials, and reports about the process of making it than the mere 15-20 minutes of the animation itself.

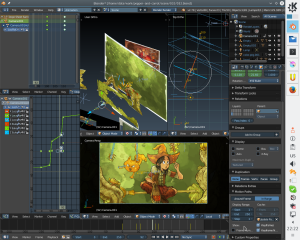

Screenlog timelapse from March 2025, which shows the tedious process of rotoscoping errors during compositing of shots. It’s almost 3X the length of the episode I’m working on, and there’s many of these. Also, it has just 6 views. Is that bad? Does it matter? Am I making it for the views..?

Why do I make these now? To some degree, they are an accommodation against my problems with “executive dysfunction”, which I’ve come to realize is a symptom of my own “neuro-divergent” personality (it’s the ADHD, basically), and the root of an awful lot of my life and career problems over the years. How it does that is a subject for another time.

But the key point I’m trying to get to here is that, while these records are nice to have, it is not about producing them as a result.

The point is the ritual of making them. In the process, I review what I did during that time interval. In fact, I review them multiple times, digesting them further each time: I make raw recordings which I reduce to dailies, including all of my activity, then, each month, I extract the most important work — production or development — and reduce that into the monthly timelapses. And then, at least in three of the last five years, I’ve made annual reviews.

This ritual has the primary benefit of improving my morale and validating my effort in an environment that doesn’t naturally do that (I am the only one available to give me “performance reviews”). It keeps me in mind of what my process has been, which helps to stay on track for what it should be now. More than once I have picked up on a research project I did, but then forgot about, because I saw it in the logs when I was editing later.

It’s just like when people copy their notes from a lecture. This is not just about making a neater version of their notes. It’s about reading and interpreting the notes to review the content of the lecture.

I’ve managed to package up the screenlog with samples of music from my free-licensed soundtrack library as a nice and perhaps relaxing product (at least, I find them relaxing). I was inspired in this largely from the “speedpaint” or “timelapse” genre of YouTube videos created by digital painters to show their process. Even the audio serves a personal utilitarian purpose beyond simply making the video more pleasant to watch: it’s a way to keep the tracks current in my mind so that I can recall them when I am considering what to use in a production soundtrack. Likewise, editing these on a daily or weekly basis is low-key practice with Kdenlive (it’s not challenging me, but it makes sure I don’t forget the basics).

And the final result does have some value in that it provides documentation. In my case, the daily logs frequently contain technical IT processes or Blender techniques that I might otherwise have a hard time doing again — and this saves the time of having to relearn it from scratch. Probably, if I had management to justify this to, I’d focus on this aspect,which probably has saved more time than the process costs me.

What I’m getting at here is that there is value in the human experience of creating art. My whole production process with its focus on open tools, open art, and free culture documentation is about the process as well as the result. AI process would put a lot of that into a black box and hide it away from us.

Okay, But Why Though?

So now we come down to one of those deeply philosophical issues: WHY DO WE MAKE ART?

Or for that matter, WHY DO WE DO ANY OF THE THINGS WE DO?

If our objective is simply to produce lots of content for the content mills, then AI is already doing a spectacular job of that. YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and other online media are rapidly filling up with what has come to be known as “AI Slop”. Low-quality, cheaply produced, soulless mash designed to catch your attention, get clicks and views, and punch up those monetization metrics.

If that’s the game, we poor humans have lost already. Fighting that is John Henry fighting the steam engine. I’m not playing that game.

So, clearly, there is more going on here which might define “real art”. What is that exactly? I may not be able to answer this question today. Maybe there is no one answer. But I think it’s an important question to ask, anyway.

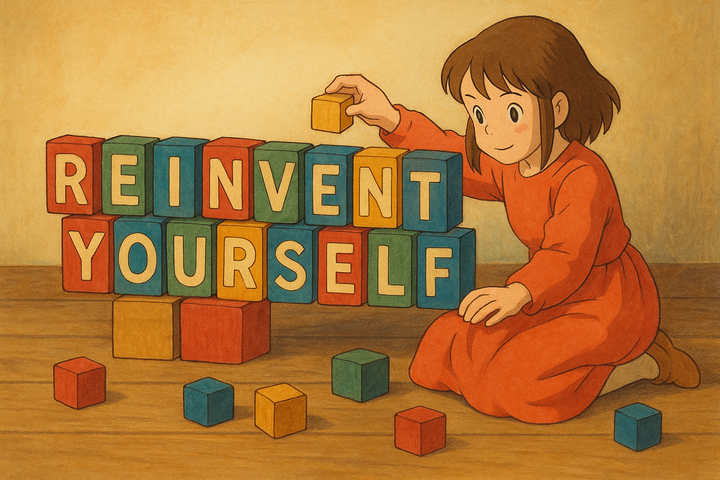

This image is just… wrong. Artistically, aesthetically, rationally, perhaps morally. The more I look at it, the more wrong it looks. It clearly has an inconsistent 3D perspective and structure, but not even in the intentional playful sort of way that an M.C. Escher illusion has. This is just slapdash — the computer missed reality, because it wasn’t really trying to achieve it. And the result is a soulless uncanniness. The character in the picture is looking off into space with a vague smile. She is neither looking at us, nor at what she is doing. And what is she doing with that block? Where does it go? What purpose does it serve? (Some of my criticism here reflects remarks by @glyph@mastodon.social).

I do not recall the source, but I do remember the remark that generative AI had made them believe in the existence of the soul — by showing them art made without one. I think that sort of captures the effect I get from this! But also from every attempt I have made at getting art out by putting prompts in. The computer is doing something, but art it is not.

And if we’re not doing art with the AI, then what are we doing? And why should we?

Another great analogy that is worth considering is the “exercise” concept. We don’t allow calculators when students are learning their addition and multiplication tables, because we are trying to teach them the math, not how to operate a calculator. Likewise, we don’t want essays or art generated by a machine, and students who genuinely want to learn how to do these things gain no benefit from watching a machine do it.

“As the linguist Emily M. Bender has noted, teachers don’t ask students to write essays because the world needs more student essays. The point of writing essays is to strengthen students’ critical-thinking skills; in the same way that lifting weights is useful no matter what sport an athlete plays, writing essays develops skills necessary for whatever job a college student will eventually get. Using ChatGPT to complete assignments is like bringing a forklift into the weight room; you will never improve your cognitive fitness that way.”

Art as a Social Behavior

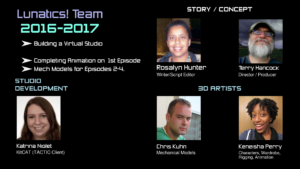

“Lunatics!” not my own personal production. The work of approximately 35 people is incorporated into “Lunatics!” episode one, “No Children in Space”. Of those, perhaps 20 have contributed actively (the rest are what I’ve come to call “passive contributors” — people who released work under compatible free licenses, but who have little or no personal connection to the project). With a handful of exceptions, I haven’t paid them for this, so this is not “labor”.

These are creative contributions. The more they contribute, the more the result is “theirs”. Daniel Fu made the character designs — our work has made them into purposefully moving characters on screen. Chris Kuhn made most of the mechanical and spacecraft models you see — our work provided him with designs, and then brought the models he made from them to life. One can shift the perspective as to who is the “creator” and who is the “labor” helping them to create. Traditionally, as a producer and director, there’s a hierarchical worldview in the industry where I get the credit (or blame!) for the whole. But I’ve rebelled against that view — there’s no way I could make this on my own. And all of this is about a story primarily written by Rosalyn Hunter.

And it’s this kind of collective ownership of the product that is a big part of the motivation. To paraphrase a description of open-source software development I once read: you give a brick and you get back a building. That’s why we collaborate.

Automation of Art and Animation

Machines and software already make up a large part of this. There’s a lot of drudgery in making animation that once had to be done by people. Sweatshops full of people (mostly women, which is another whole topic) traced penciled art onto celluloid, then flipped it over and painted the back with color: “ink & paint”, which is the basis of “limited cel animation”. Done this old-fashioned way, it took a thousand people to make a cartoon feature. Even live action films depended on editors who actually cut film with razor blades and taped them together to edit scenes (I’ve actually done this with 16mm film, by the way — it was part of my film curriculum at the University of Texas. I don’t know if they still teach that today. It was fun for awhile, but I could see how it could get dull).

Much of that labor has been eliminated by moving to “digital ink and paint” — and also “in betweening” and “key framing” — and finally by moving the whole thing from 2D drawing process to 3D modeling and animation process. As the software becomes more sophisticated and yet limitations persist, it can seem that the machines are directing you as much as you are directing them. I have heard woodworkers speak of “working with the grain”, and that is definitely a part of the machine-assisted art of animation. This isn’t new, not even with the computer age. In the 1930s, pioneers of cel animation had to work with the limitations of their process. The breakthroughs for them usually came in the form of machinery, like the massive “multiplane” camera that Disney used for decades, from “Snow White” to “The Little Mermaid”.

Demo of Multiplane camra. Janke@Wikipedia / CC By-SA 4.0

Today, of course, we can do all this in Blender, as Morevna Project did (and does) with their “Pepper & Carrot” motion comic series (based on Pepper & Carrot by David Revoy):

I would NOT want to go back to the sweatshop method of making animation, even if there is a special quality to these hands-on projects that the digital counterpart would struggle to attain. Ironically, this is because the digital method trivially produces the ideal result that the traditional method struggled to attain.

In fact, saying that is almost absurd — if we had to do it the old traditional way, I wouldn’t be animating at all. I simply wouldn’t have access to the necessary capital to pay all of that labor. And I’m pretty sure people would not volunteer their time for free to hand ink and paint cells! That is definitely work, which automation has eliminated the need for.

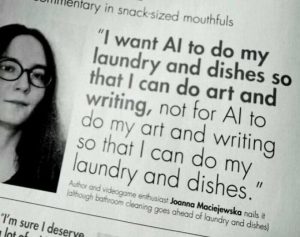

And so we get down to this meme, I’ve seen on my social media accounts several times now:

What we’re looking at here is a distinction between “labor” that we don’t enjoy doing, except for the money that it earns, versus creative work that we do as much for the fulfillment as for remuneration. Indeed, in the context of a free culture project, monetary remuneration is likely to be non-existent, so it’s really all about the fulfillment of creative expression.

So where does AI fit into animation? Is it just another kind of automation?

Is it like the introduction of the film camera which made photorealistic renderings trivial?

Or like the computer that allowed us to eliminate the steps of hand tracing and painting cels?

Or like in-betweening software like Synfig that allows animators to work purely from key frames?

Or like Blender, that automates the entire drawing process, moving the artist to designing and animating models in a 3D space?

Or is it like none of those things?

I have seen some examples of limited AI image generation use that I might consider acceptable, because they have sufficient human control. For example, I have seen AI used to fill in rendering on a penciled drawing, based on other rendered drawings or other parts of the same drawing. I have not had a chance to try this kind of technology, but it does at least seem to have some potential for artistic use. A sort of super-sophisticated photo-restoration tool. If such tools emerge, I’d be a fool not to take advantage of them, especially on an animation project, where automation is a given, anyway. But I’m certainly not interested in letting the machine fill in my whole blank page.

Credible Lies and Incredible Truths

Another major concern is the political use of AI, particularly the creation of AI “deepfakes” to pose messages as if said by another (possibly unwilling) person. They are now often used in political advertisements.

US political ad, using a deepfake of Kim Jong Un.

These are potentially pretty scary. There are examples of fake videos at disaster sites, defaming various authorities or politicians, while lionizing others. It’s quite easy to put words in someone else’s mouth with this technology.

Of course photo tampering is not new, and software to manipulate digital images (most iconically, Photoshop, but Gimp or Krita will do just as well) has made it far easier and far more convincing.

On the other hand, one of the ways that we immunize society against the dangers of such deception is through the benign creative uses of such technologies in film special effects, animation, and other kinds of art. Once people see that a technology can be used to create pure fiction, they begin to understand that they should be more skeptical about what is presented to them as fact.

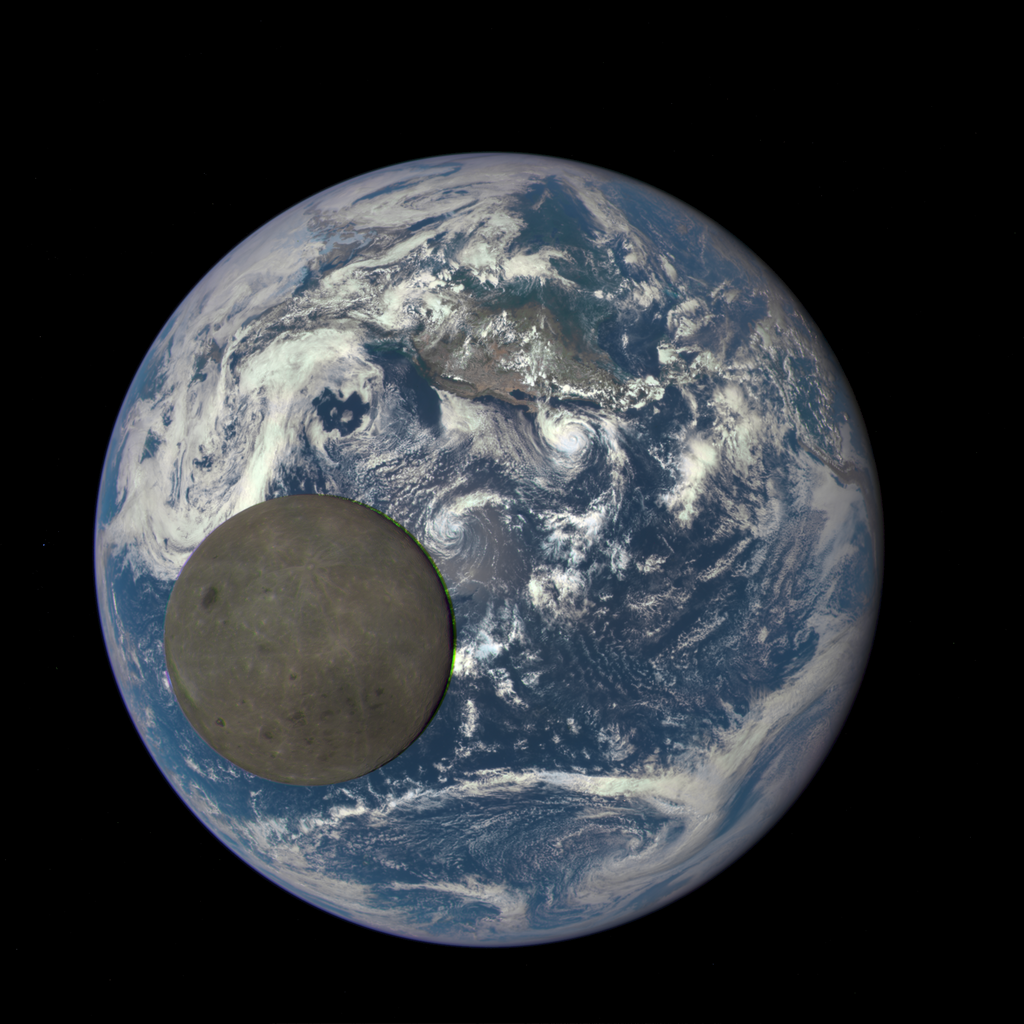

Of course, there is a negative side to that as well. People begin to be too skeptical of images that are 100% real. I have encountered a number of cases of people disbelieving real space images because they seem “too perfect” or violate some expectation that they have developed, perhaps from historical imagery taken with less sophisticated cameras.

100% real footage from the HD camera on JAXA’s Kaguya (a.k.a. SELENE) orbiter. I saw many comments from people believing this was composite imagery. But it’s just a super-sharp image. There’s no atmosphere on the Moon to create any distortion of the Earth as it appears over the horizon. But in an age of accessible photo-manipulation, it’s not surprising that people get skeptical.

And yet, so many people thought THIS next image was a real photo when they saw it on social media or news sites, that NASA had to publish a statement emphasizing that it is not! Of course, to me, with astronomy and planetary science education, it seems pretty obvious. The spacecraft is not designed to take images like this, could take very few images during final descent, and there are other things — the clouds look a little too puffy to me, for example. And Cassini doesn’t have a proper color camera — it has a filter wheel, just like Voyager did. Successive B&W images are put together to create color. But at this speed during final descent into Saturn, that would clearly be impossible, the scenery would be changing too quickly. But it’s a great artistic impression.

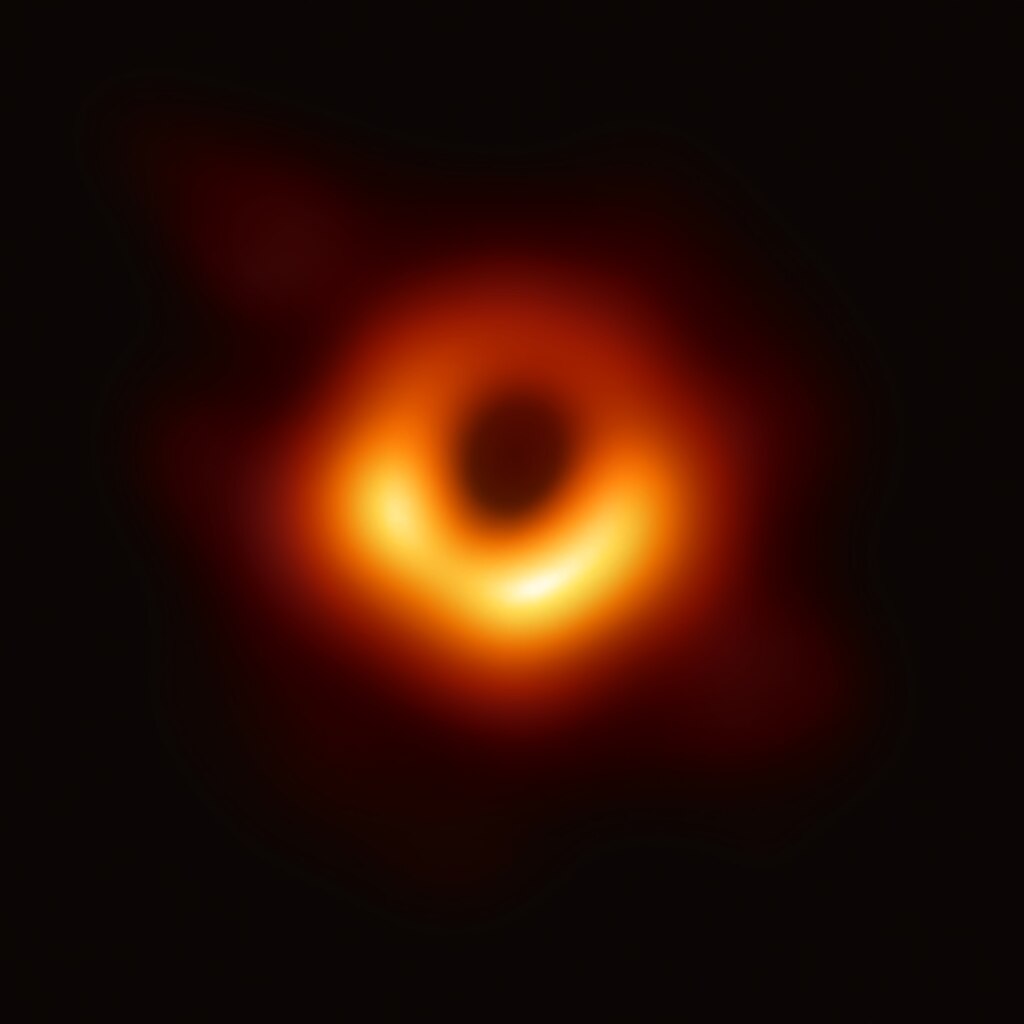

And there is a middle place. The image below was created from radio telescope data to be an accurate image of the accretion disk and black hole at the center of the nearby galaxy M87. But it was synthesized by AI image processing!

This is a kind of “super-resolution” technique, where we try to reconstruct the most plausible “true” image of something we do not quite have the resolution to directly image. Basically, a diffusion-like AI technique would be used, constrained by the available millimeter-wave radio telescope data from the Event Horizon Telescope. This constructs a “super-resolved” image — that is, one that is higher resolution than the raw data allows by simple Nyquist sampling and deconvolution. This is clear enough from the public presentations, though to be fair, I haven’t read the papers and am not really familiar with the software techniques they used. But the point I’m making here is that AI can help us to see the truth, if that’s what we use it to do, rather than making up lies.

Is it “Burning Up the Planet”?

This, at least, I think I can dispel quickly. There a lot of claims that get traction on alternative media like the Fediverse, where critics of AI talk of “boiling the oceans” or “using the energy of a small nation” to run AI software. These claims are largely myths, or at least greatly exaggerated.

I know people using Stable Diffusion who run it locally on what are essentially gaming graphics cards on their home computers. If these uses of AI are “boiling the oceans” with their energy consumption, then we need to have a conversation about the industry and culture of computer gaming! Because clearly a lot more energy is going into playing games.

The point is, this clearly shows this is not a fair assessment. Some AI models are wasteful, particularly the major US competitors like OpenAI, ChatGPT, and Grok. But other LLM platforms are being made that greatly reduce these costs.

In fact, it seems like the US LLM promoters are using exaggerated notions of power consumption as some kind of bizarre marketing ploy, which may be why they aren’t fighting these myths. It seems like there’s a kind of “pump and dump” happening here, where entrepreneurs try to get everyone to buy into AI as “the next big thing” so they can cash out on that investor hope, before the ugly truths come out.

Which is sad, because, as I see it, the AI technology isn’t really that ugly. It’s just not the snake oil panacea they are trying to tell us it is. I’ve seen a lot of potential uses for the machine-learning-based recognition (it could really improve my asset management if I could incorporate this). And I have identified some ways that I think generative-image AI could be used constructively, even if I’m not sure I want to do that.

So, I can sum up my objections to this argument very briefly:

- Unfair singling-out: ALL computing has power costs, AI is just one of many uses.

- In general, computing costs taken together are still much less significant than industrial uses.

- Projections of AI usage, and therefore cost, are highly unrealistic. Some of those projections are puffery from the AI software developers themselves.

- Most of the costs for AI fall under training and model-development, not queries. It’s a front loaded cost, like building out solar panels and windmills. That’s not a fair comparison to on-going costs of the status quo.

- Newer AI models have been made for less energy cost, and it’s likely this will continue. It’s partly because they can build on prior model development (which is a social good, even if the original companies don’t like it).

- There is some conflation of Stable Diffusion (SD) model development (which makes images) and Large Language Model (LLM) development which writes (but now is also connected to SD for illustration in many cases. It’s possible the SD systems are far less energy intensive, which would explain why people can run it on their own computers. But I doubt that’s really true).

- Note that rendering 3D animation and art is already a fairly computing-intensive process without using Stable Diffusion, so the difference is not stark. And the AI might reduce the number of repetitive iterations some artists make (though I’m not sure it would for me). We do a lot of rendering of trials and intermediate steps as it is.

Finally, though, whenever somebody tries to raise “cost” as their primary objection to a benefit analysis, that’s a red flag. It means they have no arguments against the benefits. It’s a polemical technique to try to imply that there are no benefits. I’ve learned this from many years of US Republicans arguing that we “can’t afford” space exploration, scientific discovery, medical research, social security, hospitals, food assistance, or even universal basic income. Considering how much we spend on weapons systems, advertising, tax breaks for billionaires, and football stadiums, it is absolutely clear we can afford them, and that was not the question. The question was about benefits. Trying to switch to costs is a deflection.

I think this particular argument is something that people use because they had success with it against crypto-currency. That’s a whole other topic. Many of the same counter-arguments apply. But as far as I have been able to tell, this argument was largely specious there, as well. The primary harms of crypto-currency have not really been about energy consumption. It’s mostly about market-distortion, a lack of practical applications, and exploitation through speculation. But of course, I acknowledge that in both cases, significant resources are used. If the benefits aren’t significant (the foregone conclusion this sort of polemic is trying to get us to accept by sleight-of-hand instead of honest argument), then of course they would cost too much. But you haven’t proven that, and it’s deceitful to argue in this way.

Is it “Wholesale Theft”?

This criticism kind of annoys me, especially when I hear it from free culture advocates and copyright skeptics. It seems a little hypocritical to me. What Stable Diffusion is doing is a long way from a direct copy. It’s learning properties of the art it is exposed to, and using that to create new images. I often find the results mechanized, soulless, and cliched. But copies? No, not unless you really go out of your way to get it to spit out a copy of something you know is in the training set. I’ve seen people do this as some kind of “gotcha”, but it doesn’t make any sense.

You can use more conventional digital painting or photo manipulation software to copy an existing piece of art. You can slavishly draw a copy of an artwork you see — and the result will be unoriginal, but generally not a copyright violation.

Likewise, the alphabet and the words in dictionaries are things we all agree are and should be free. But you can put them together into a copy of a famous writer’s work. When you do that and only when you do that, you violate copyright. Is this not protection enough? Do you really want to turn copyrights into patents on styles, composition, and story ideas? Personally, I think that would be a nightmare.

Hollywood lawsuits over ideas for movies and similarity of screenplays are already a nightmare that seems to me like it’s only a benefit for the lawyers. Any real artist or writer knows the real work isn’t in the ideas or tropes or look, it’s in the execution of the whole concept as a finished work.

And a free-culture artists ought to understand that this obsession over restricting the right to copy things is crushing us, culturally, even as it is. Copyright has already gone too far. We don’t need it to get worse.

What we need, if we’re being honest, is a better way of remunerating artists than installing meters on the flow of information.

So this seems like a pretty specious argument to me, even if I don’t take into account the fact that I think copyright is already far too aggressive and broad in scope. I certainly don’t want people to lobby for a more restrictive copyright that would extend to make fan art and illustrations based on copyrighted media illegal.

There is one decision, made by the US Copyright office that I really do approve of, though: they refused to allow copyright on works created entirely by generative AI. What the AI generates has the status of clipart. You can use it to make a copyrighted work — but only if you contribute significant creativity to it. The essence of this decision is that copyright is for humans. And if no humans were involved, then no copyright exists, leaving the work in the public domain. This applies even for a non-human living being (I fear this might be an unfortunate precedent if applied centuries from now, but I don’t expect copyright will still exist then, either).

Far more obviously, copyright does not apply when a work is the result of a machine working on its own, no matter how “artificially intelligent” that machine is. A sticky case for this is what happens legally with a photograph of a public domain work. Such as a photo-reproduction of a painting from the 19th century. Taken flat-on, the photo is deemed to add nothing to the work (at least in the USA and several other jurisdictions), but if you take a photo of a PD painting in a museum (such as the image above), this is then a new work. The photographer is credited, because they are responsible for the framing and composition of the shot.

This makes sense to me, and it continues this theme of the human input to the image being what makes it a copyrightable work. When a machine generates an image from a short textual prompt, that is just not enough human originality to make it reach the threshold for copyright.

Conclusions: Yeah… No.

At least for now, I can’t really persuade myself to use AI generation in any significant way in my animation workflow, but I don’t think I can support a conclusion that doing so is categorically unethical or immoral. I think there are good aesthetic reasons for my choice and good process reasons.

Arguments about energy consumption or copyright infringement, however, seem to lie along a spectrum from utterly specious to greatly exaggerated. I think these arguments are merely rationalizations by people who’ve already made up their mind and are trying to find something concrete to back them up. So, basically, I have no basis to shame or scold you for using AI to “generate art”.

I’m just not convinced that’s really “art”. And personally, I just don’t love it. It’s fun to play with, but I just don’t want it in my project.

Whenever I see AI generated art, I’m just struck by how soulless it seems.

Even if I use it for the limited uses I suggested in the first section (backgrounds, textures, screen dressing), I find it inferior to other methods. A human would put more systematic patterns into textures, but the AI always seems a bit melted and/or muddy to me. It often picks dull colors. It seems generally purposeless. The screen dressing is probably the greatest success, because it does kind of look like an impressionistic painting of a screen, but it’s possible to get a pretty similar effect with just some shapes in Inkscape.

My second objection is about the process of art and how it feels to make it. It just takes the fun out of it. Art departments have snuck easter eggs into their work for a very long time. A notable example is the mutual respect of the artists for the Japanese space-opera/mystery anime “Dirty Pair” and the art departments for “Star Trek”. It’s obvious why they’d feel this way — the two shows have a similar sort of universe and level of development. And there is something pretty cool and very human about this cultural exchange!

If they’d just filled up these background elements with AI Slop to save a little effort, we’d be robbed of this behind-the-scenes experience, and that seems like a real shame. I’ve been having fun doing detailing in “Lunatics”, even if it is very time consuming. There are easter eggs in “No Children of Space” tagging several of the media and literary science-fiction stories that I’m a fan of, and I’m glad I did it that way.

I apologize for this long rambling essay, but I think this is where I can finish up: Without AI, art is just more fun.