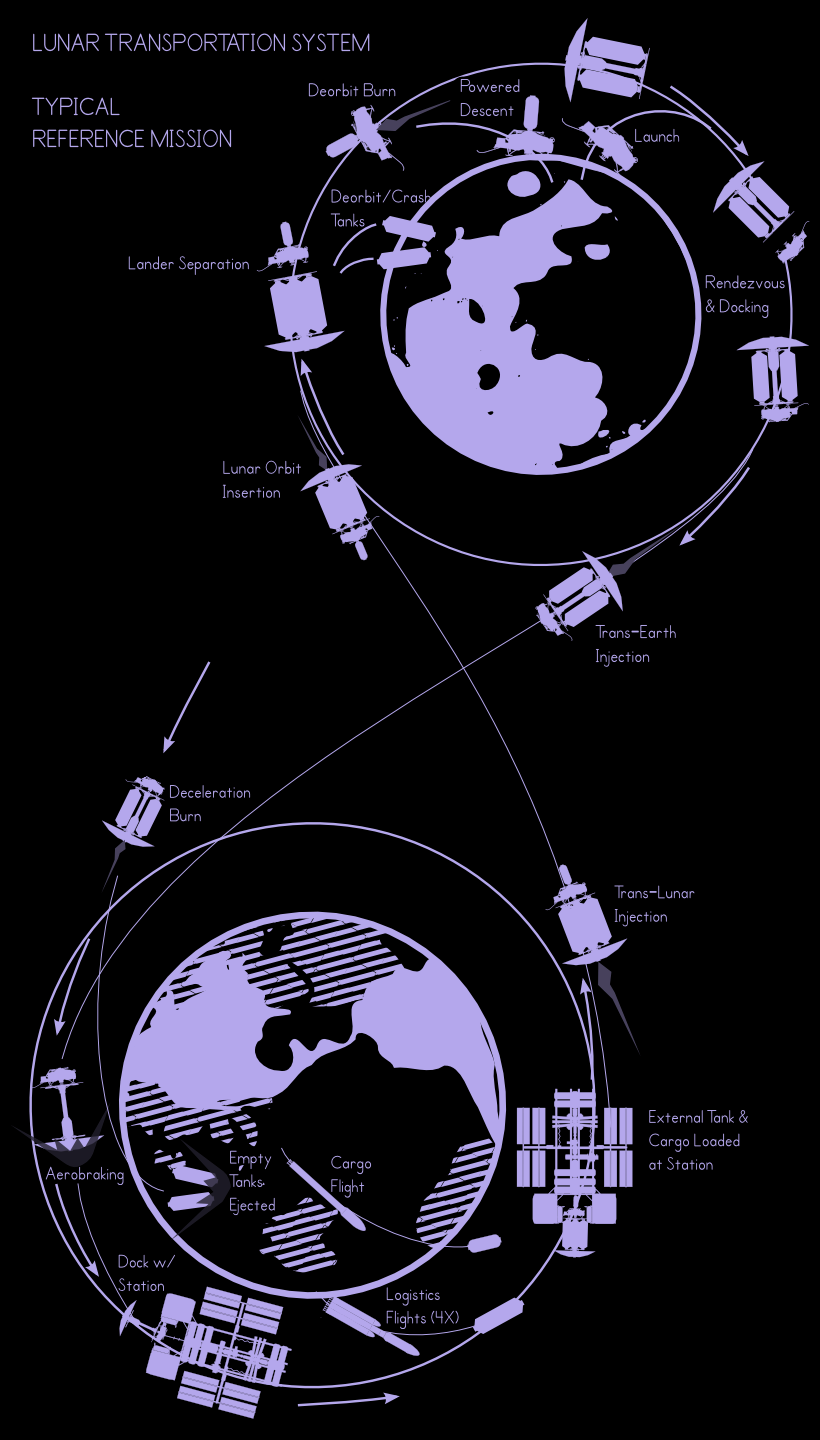

Lunar Transportation System

One of the main unique features of the Lunatics concept is our commitment to keep things driven by

real space technology and resources. This meant that we had to explain not only how our Moon colony worked,

but also define exactly how it was supplied.

This kind of logistical consideration is actually central to any real moon colony design, and

so we needed to define what it was in order for our Lunatics plots to make sense. That’s partly why we

decided to demonstrate this system in our pilot episode. Thus, Hiromi, Georgiana, Tim, and Josh all come

to the colony aboard the “Lunar Transportation System” or “Moon Shuttle”, which is the first major

science-fictional element in the series.

A Space Shuttle — But for the Moon

As a guiding principle, I start with the idea that in our 2040 era, we wanted the Moon to be “about as

accessible as Low Earth Orbit is today”. That meant providing a standard, regular system of resupply that

could be operated several times a year (but not more than that). I also wanted this to be an American design,

similar in concept to the US Space Shuttle (which has the technical name “Space Transportation System” or “STS”),

with various compromises of reusable and disposable components.

I did not necessarily want this to be my ideal concept for how a Moon Shuttle might work,

but rather to be a plausible system the US NASA Industrial Complex contractors would really build. Thus, the

system is on the conservative side, relying on proven technologies like chemical rockets and staged tankage,

rather than exploring exciting (but risky) new concepts like space tethers or nuclear propulsion.

I also wanted anything we used in the design to be something that was at least on the drawing board somewhere,

or in the laboratory. I wanted to avoid making up a lot of stuff. And I wanted the math to make sense (at least

on a back-of-the-envelope level). So, I did some research into papers from Lockheed and Boeing on Moon and

Mars spacecraft designs as a starting point.

So with that beginning, I came up with the “Lunar Transportation System” (“LTS”) or “Moon Shuttle” as

the key element in the design process for the lunar colony and how it would operate.

Design Process

Several things become immediately apparent when you look at this problem. The first is that it take an

awful lot of fuel to move sizable cargoes to the Moon. And that means coming up with a way to launch all of

that fuel into low-earth orbit. I also wanted this to be a natural outgrowth of our current space capabilities.

So, I decided to look into some launch services that already exist.

One paper I read described an on-orbit refueling process. But as I started to think about this, it made

less and less sense to me, because the fuel transfer process is slow and lossy and complicated. Meanwhile,

what happens to the tanker flight? Typically, it would be a disposable tank launched on an expendable launch

vehicle — you’re just going to let it burn up in the atmosphere. So I thought, “Why bother transferring the

fuel?” Instead, just design the spacecraft to be able to swap fuel tanks directly. Throw away the old

tank after using it, and just attach the new tank after it is launched. With some care, all of the expensive

equipment can be put on the reusable part of the spacecraft, making the disposable part as cheap as possible.

The result is a bit like the External Tanks used on the US Space Shuttle. And this also gave me some more

inspiration, because, just as with the Shuttle ETs, the LTS tanks could be salvaged and reused in some cases,

to provide cheap building materials for colonies. And in fact, the oxygen, hydrogen, and water tanks used for

the fuel-cell system on our ISF-1 Colony are all recycled LTS tanks.

Likewise, much of the modules that I used in both the Iridium Station and ISF-1 Colony designs are intended

to be modules originally developed as part of the LTS, as well as of our updated “Space Station Alpha” (which

is meant to be the future, extended and renamed International Space Station).

Although other, more expensive, fuels are possible, I opted for the basic liquid hydrogen / liquid oxygen

(LOX/LH2) combination, both because this is more efficient, and because I found papers in the same search which

described newer technologies for using these cryogenic fuels on longer missions. Early missions didn’t use them

because they are harder to store, and would tend to evaporate away or expand. But it’s possible to bring the

cryogenic plant along with the mission, and that’s how I decided that the LTS would work.

The design also incorporates expanding, self-deploying memory-polymer trusses and high-temperature ceramic

foam materials which are currently just laboratory projects, but which should be practical engineering materials

by the 2030s.

The lander part of the LTS (which features as our newsletter cover this month), started as an adaptation

of a “flop down” lander concept developed by Artemis Society International in the 1990s as part of their

“Moon Hotel” concept. This was such a bizarre idea, that I felt it would be a lot of fun to use the same basic

concept in our show. The main insight is that, because of the Moon’s lower gravity, it’s possible to simply

let the cargo (or passenger) module, swing down to touch the ground. This means it can be stored in a centered

position directly above the main engine during flight (much to be preferred for center-of-mass reasons), and

yet we can deliver it straight to the surface for easier loading and unloading. Watching this in operation

will provide some nice visual interest for our landing sequence in the pilot.

Overall, I think the LTS is a great example of how holding yourself to a certain standard of realism

can really boost the creativity and originality of the story and setting. The final logistics concept for

the LTS is illustrated below (adapted from our Writer’s Guide, Volume 1).

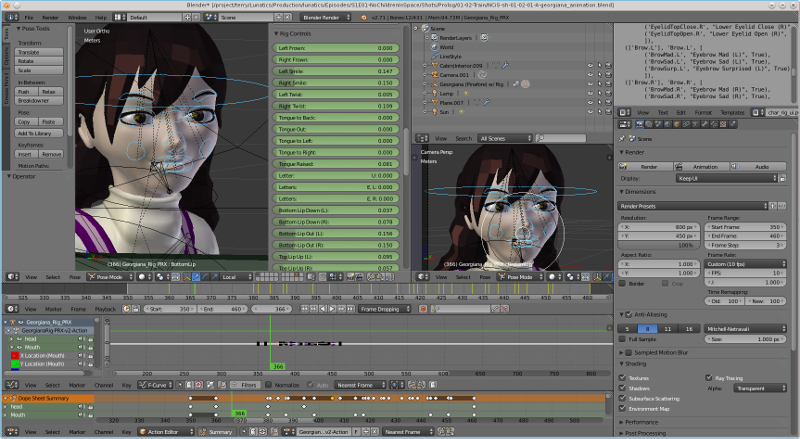

Blender’s NLA Editor

Last month, I showed you a sample of the basic character facial animation that I’ve done. That was

done using Blender’s Graph Editor and Dope Sheet. To give you a taste of how that’s going, here’s the

“Learning Curve” video I posted with successive trials of facial animation for Georgiana:

At this point, I’m beyond that point, but I’m trying

to combine motions together into a combined performance using Blender’s “Non-Linear Animation” (“NLA”)

Editor.

This is my first experience with the NLA, the “Action Editor”, and the process of combining actions

in Blender. My impression is that this is a great workflow concept, but — and this is a big “but” —

the NLA Editor seems to be somewhat immature. Either that, or I don’t yet understand how to do important

things with it. There’s also not a whole lot of information available on it online in the form of tutorials,

so I’m well into having to do trial-and-error learning with it.

For example, my current dilemma with the NLA is that it’s hard to combine some actions in a sensible way.

I animated the character breathing — with a gentle up and down movement involving head and torso movements.

But the character is leaning over to look out the window, so the base point for these movements is not the

neutral “T-pose” for the character, but this leaning position.

I then want to combine this with the character’s slower movement from position to position as she looks

out the window in different directions. The parts of the movement that involve different armature bones present no

real problem, but the shared bones (head and torso) do not combine well. I have a choice of “Replace” or

“Add” for the movements, with varying degrees of influence. To “Add” the movement seems like the more obvious

choice, but doing so means adding the rotation from the neutral “T-pose” as well as the deltas (change in

position) due to the breathing motion. So the character jumps to an unnatural position if I do that. Alternatively,

I can “Replace” the motion, but then the character returns to the neutral position that I originally animated

the breathing from. Of course, I could re-do the animation from the “T-pose” in order to add it, but the

movement doesn’t make as much sense in that position, and it would be harder to animate correctly.

For this problem, a more sensible combination rule would be something like “Add Deltas” — subtract out

the average position of the bones and then add only the frame-to-frame variations. Without this, I need

to find a workflow that will let me manually subtract out the neutral position from the breathing motion.

Various possibilities exist, such as creating a special driver for the breathing motion in the rig. But

it’s not clear yet which is the best solution, and I will have to spend more time figuring that out.

Our First Minute (and a Half)

We have now finished approximately one minute and a half of animation for Lunatics. Here’s a sneak peek at what is finished (plus about 10 seconds of draft video so as not to cut the voiceover off in the middle of a sentence!):

Direct link: minute_and_a_half.webm. The narrator is Melodee M. Spevack, who has been the English language voice of characters in a lot of very popular anime series.

We’ve also tested just about every aspect of the production process, and this has given me better perspective as both the director and the producer on this project. Some things have gone extraordinarily well. Others are still wanting, and our production is well behind where I’d like it to be because of some of those.

Considering that we have almost no money and only four or five people working on the project in their spare time,

it’s pretty amazing that we’ve gotten as far as we have. On the other hand, it’s clearly not where we had initially

hoped to be this long after we started. And the time delay has significant costs. In addition to the usual risk of

people simply leaving the project, some things are intrinsically time-dependent. For example, the actress who voiced

“Georgiana” was 9 playing 7 in 2012 when the recordings for “No Children in Space” and “Earth” were made, but she will

be 12 in 2015, and should production of the Pilot stretch out over this year, we may not get to episode 3 (“Cyborg”)

until 2016, when she is 13. Obviously her voice is changing, and it’s already pretty different from before (this is

bad part of casting a child to play a child, obviously).

But even for the adult actors and Blender artists, the passing of time means other projects start to take priority

and it’s hard to keep a team together. This really puts the pressure on me to release a Preview and then the Prolog,

so we can hopefully get some more support for the project. On the other hand, if the animation looks terrible, then

it could actually drive people away. So it’s a sticky situation.

As things stand, with the present project team, and me doing most of the animation by myself, it’s reasonable to

think the Patreon Preview can be finished before the end of the year. There isn’t much lacking for that — I still

have to get past the hurdle of animating Georgiana with the NLA editor as described above. And I have to do some

additional body animation (though that may be simpler). There’s also a couple of exterior sets to finish. But the

remaining animation there is pretty simple stuff. So I really do think I can do that.

Finishing the Prolog, though, is clearly going to take well into Spring 2015. At this point, I’m just hoping we

can get it out by “Yuri’s Night” (April 12), following our “space holidays” targets. At the same rate, it might

be possible to get “Pilot – Act 1” out by “Moon Day” (July 20), and “Pilot – Act 2” by “Space Week” (October 4). That

does depend on getting a lot of interior sets finished, though.

On the other hand, if we can start to raise money and/or interest in contributing directly in early 2015, it might

be possible to speed things up. I’ll give that more consideration in January — hopefully after releasing the Preview,

and seeing what reaction that gets.

Project Needs

I’ll be putting out formal calls for additional help on the project after the Preview is completed, but I can

already outline what we need:

- Character Animators: I’m learning to do this, but even if I were an expert, the project still

calls for so much animation that more will definitely be needed. - Plan Drafters (2D): So far, I have been the one who looks at ground photos and satellite images

and puts together plans for exterior and interior sets. However, I really could use help in this area. This does not

require Blender skill, but skill with a 2D application like Inkscape (though any drawing program would do), and the

ability to interpret photos. Good spatial reasoning skills are needed for this, but otherwise it’s not really hard —

just time-consuming. - Set Modelers: We need additional help building interior and exterior sets. This requires only

basic Blender modeling skills. Interiors are generally boxy, with surface texturing for floors, walls, and ceiling.

Exteriors are sculpted landscapes with buildings and other features added. - Set Dressers: We’re using a lot of stock 3D models from BlendSwap for basic props and set

dressing. But these need to be adapted (“tooned”, I like to say) to our shading and materials style. And they

need to be grouped properly for library use. In a few cases, there is no good stock model, and new ones have to

be made. The models also have to be linked and positioned into our sets. Again, this is not hard stuff — it

requires only basic to intermediate Blender skills. But because it is time consuming, it really eats up our

schedule.

Credits for the Video Clips:

(Converted from December 2014 Patreon Newsletter, 2025-10-23)

| Character Design | Daniel Fu |

| Character Model | Bela Szabo |

| Character Wardrobe Armature Rig & Weight Paint |

Keneisha Perry |

| Textures & Materials Character Animation |

Terry Hancock |

| Passenger Train Car Model | Chris Kuhn |

| Narration from Preview/Prolog/Pilot | Melodee M. Spevack |