It’s been over ten years since our project launch on Kickstarter, which is probably as good a date as any to call the “beginning” of the “Lunatics!” Project, although its origins actually reach back in various ways as far as 2000 (the germ of the story) or 2009 (the idea that we might actually be able to produce it as an open movie) or 2010, when I posted the first essays into the project in my Free Software Magazine column.

So this seems like a very good time to reflect on what we hoped to achieve with this project, what we have achieved so far, what went wrong, what went right, and what we hope to achieve in the future.

This is Part 4, addressing the problem of how to publish a movie on fixed-media, using free-software tools, in a way that is aware of the limitations and strengths of free-culture / free-software film production. This is a technical side-story, with some important parts happening in 2012, but still developing in 2025. It’s part research, part development, and part planning for our next steps.

What Are We Selling?

This is a question that I keep coming back to, when thinking about sustainable production in a free-culture / free-software world. So much of what we’re doing is about the production itself, with a focus on reducing direct fixed costs (no software licenses, no up-front licenses on assets, etc). And then again on eliminating restrictions to sharing and distribution (free public license, allowing anyone to share it as they like, eliminating the notion of scarcity).

But scarcity is essential to the notion of selling a product or service.

There are a number of different ways of answering this question. Some of which directly challenge the whole capitalist model of economy, some of which require compromises on the central assumptions of free culture and/or free software. The easiest to understand, though, are the ones that simply offer to sell authentic or official or endorsed products from the people who make the film.

Nina Paley and Question Copyright had pioneered this approach with “Sita Sings the Blues”, and it pretty much worked. Despite the film itself (the digital product) being “free” in both senses of the world — available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license (initially, and then later dedicated to the Public Domain) and being free to download from the Internet Archive.

And these products sold. Paley lumped all of these into the category of “containers” for the art, which were scarce and therefore could be sold.

I would prefer to divide them into several categories, but for this article, I’m going to focus on the most “container-like” of the products, which is the fixed-media delivery format for a film. These are “containers” in the most-literal sense that they contain the main art work — the film itself, in a viewable format, and yet are physical products you can hold in your hand.

If you think about selling a book, it’s not especially hard to define what exactly you mean: what constitutes the “genuine article”. We classify books into more specific categories: paperback, comic, hardcover, etc. One thing all these formats have in common, though is that you can read them without any mechanical or electronic assistance.

And we do have “e-books”, which is just the data for the book in an electronic format (of which there are several, including PDF (closely-coupled to the print form of the book) and epub (which emphasizes the flexibility of the electronic format, since it is basically just a specially-formated HTML page with supporting files in a zipfile).

With movies, though, there really is no such genuine, tangible format. The closest might be the film reel, with literal analog photos of each frame with the soundtrack alongside. But even this can’t be viewed without the assistance of a projector.

And it’s been a long time since film reels where the main way to distribute movies. Even cinemas have gone digital, receiving and project films from digital data, rather than literal film.

Physical Fixed-Media for Movies

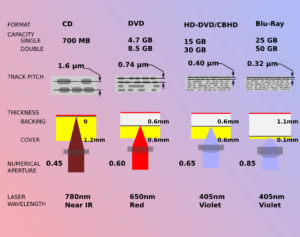

The most obvious form at the time (in 2012) was the DVD (“Digital Video Disk”, later revised to “Digital Versatile Disk” by marketers who wanted to emphasize that they could hold other sorts of data than movies). But it was already a format that was beginning to show its age: high-definition television was already becoming the norm, and DVDs only supported the standard NTSC 720×480 resolution (same for 4:3 or 16:9 “widescreen”, but with different pixel aspect ratios). This is considerably below the resolution of 720p “HD” or 1080p “Full HD” television monitors, and likely below the resolution we’d make available for streaming.

(Credit: John A. Ward / CC By 2.0)

Needless to say, it seems weird to offer collectors an inferior form of the video, just so it will fit on the DVD standardized fixed-media product.

The commercial media industry was already pushing “Blu-Ray”, which has since (by 2023) made substantial headway, and is now a moderately-successful format for collectors, despite its substantial faults.

For the collectors, the only really important things about Blu-Ray releases are their high-resolution and their “authenticity” — pretty much the same selling points that hard originally made DVDs popular. They do allow marginally more “extras” content, but not really in a way that substantially extends what DVDs can provide, from the collectors perspective, though some of the features can take advantage of the substantially larger amount of data storage.

The best properties of optical media for publishing movies are that they are inexpensive, can hold a lot of data, and are highly durable. It is estimated that a conventional, commercially-pressed optical disc (CD, DVD, or Blu-Ray) will last about 1500 years if properly stored. Even if the surface is damaged by scratches, it can be polished to allow the data to be read again. About the only thing that will really destroy them is breaking the disc itself or overheating to the point that it starts to melt.

For the publishers, of course, the main selling point of Blu-Ray was the even-more-rabid “Digital Rights Management” regime that Blu-Ray provided, giving even greater ability to crack down on the imagined boogie-man of piracy that is no more relevant now than it was then.

Blu-Ray movies still get ripped and shared on pirate movie sites online, because of course, this DRM is no impediment to dedicated pirates.

But it does create obstacles for viewers wanting to view their legally-obtained movies in whatever country on whatever platform that they wanted. It makes the product worse in a way that gives publishers more control over their customers.

But not, of course, the hydraulic-monopoly level of control they would soon have over titles released through digital streaming services!

So, Blu-Rays continue to face competition from the DVD format (which appeals to customers more interested in control over their media and less fussy about resolution) and streaming (which has excellent resolution, convenient access for customers, and provide absolute control to publishers who can now revoke access to their own products to avoid having their new titles compete with their old ones).

For archivists, collectors, and fans of older media, however, this new situation is utterly untenable. Streaming robs them of even the tiniest bit of control over their film libraries; the only copies that can be relied on are the inferior resolution DVDs; and the Blu-Ray copies which provide higher resolutions that collectors care about, are extremely fussy to preserve.

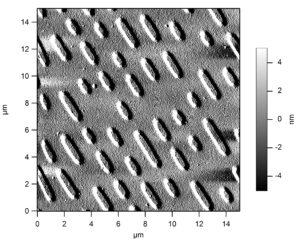

Even the shelf-life of a Blu-Ray disk is reduced, due to the thinner protective layer that is essentially to reading the finer data on the disk (the pits on the Blu-Ray disk are, of course, smaller and closer together, just as the pits on a DVD are smaller and closer together than those on Compact Discs (CDs)).

This is the status of commercial fixed-media for movies as it was in 2012, and it remains nearly unchanged in 2023.

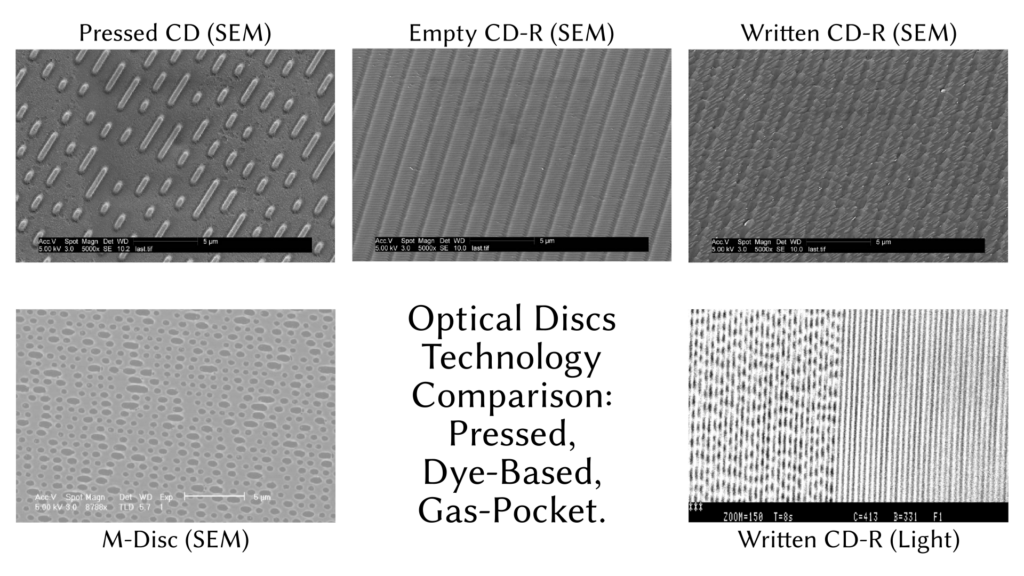

The commercially-pressed versions of CD, DVD, and Blu-Ray formats are all impressively durable, if they are kept well. But they all share one major fault, from the point-of-view of small publishers: they are read-only. There is no way to write new data to them, and they cannot be conveniently reproduced on a one-at-a-time basis. As a practical matter for publishing, you should expect to print at least a 1000 discs if you are going to use this method. Below this, the cost is basically the same — close to $1000, even if you only need a single copy.

This is because they rely on an assembly line process in which a master is used to press the disk data layer, and then protective layers are glued onto it.

You can’t back your data up onto this, and you can’t burn a single movie onto it.

Dye-Based Media

So, the industry introduced “work-alike” products that are, to this day, marketed as if they were the same product: dye-based CD-R, DVD-R, DVD+R, and BD-R media.

(Credit: Robert Silverwood / CC By 2.0)

These are the disks you use if you need to store a bunch of backups from your computer, or burn a copy of a Linux distribution. Or, indeed, to make copies of DVD movies from the digital originals.

In terms of archival storage, however, they are considerably inferior!

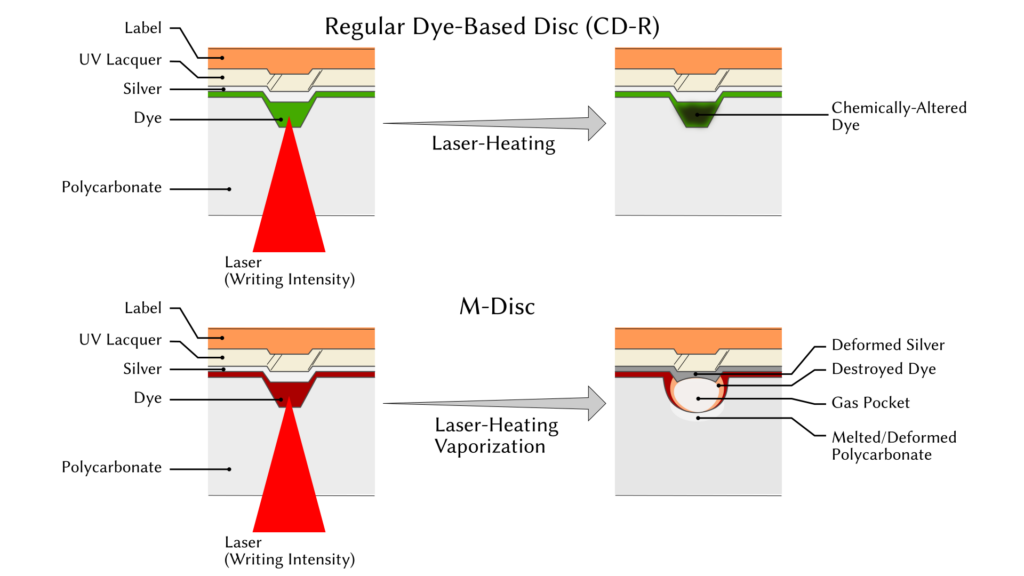

In place of the pits in the pressed disk media, there are patches darkened by a chemical reaction. You can think of them as “scorch marks” left by the laser, when the power is turned up to “burn” a disk (a fairly accurate term). This mechanism does cause some surface deformation, but the data doesn’t exist as a deformation of the disk. Instead, it is represented by chemically-distinct segments along the tracks on the disc surface.

However, they can be read back by the same laser reading mechanism that works for the original pitted disks designed for mass production. And thus, you can put a new CD-R or DVD-R into a player designed for CD or DVDs, and play back your one-off created media.

But you can’t rely on that working for the long lifespans promised for the commercially-pressed media. In fact, it has been estimated that these discs can only be relied on for an average of about 25 years. As that deadline approaches, it would be prudent to rip the disc to a new medium to protect the data.

Millenniata M-Discs

Fortunately, there is yet a third class of optical disk media, available for single-layer DVDs in 2012, and by 2023, available in 25 GB single-layer Blu-Ray Disc compatible sizes, which was developed by a start-up, called Millenniata, whose focus was on creating stable archive media for organizations that want to have long-term storage for their data.

Unfortunately, the merits of this more-expensive one-off format, are harder to communicate to customers and have a much more niche market. A more-cynical argument can be made about companies who create durable products always being inherently more difficult to keep in business. As a result, the start-up company, Millenniata, folded some time ago.

Fortunately, they sold their technology to established media companies, so it is possible to purchase “M-Discs” from some major media companies, such as Verbatim. I know that in 2023, the Blu-Ray compatible M-BD-R discs are definitely available. The smaller M-DVD-R discs are hard to find, and may no longer be produced.

This will become important for our own small-but-important market niche.

Writing to these discs does produce physical pits — essentially air pockets, which are much more durable than the scorch marks on dye-based media, and can’t fade. The writing energy from the laser in M-Disc compatible drives produces these pockets.

Roughly speaking, if you imagine the data on the commercially-pressed optical discs to be neatly-dug holes, and the data on the dye-based media to be scorch marks on a flat surface, then the data on the Millenniate M-Disc media are “bomb craters”. They aren’t as neat under a microscope as the commercial discs, but they read like them, and they are more durable and long-lasting than the dye-based media. Indeed, they should have about the same shelf-life as the commercially-pressed discs.

They are roughly three-times as expensive, though: you can expect to pay about $3.00 per disc for M-BD-R media. On the other hand, while the original M-DVD discs required a special writer drive, a drive designed to burn standard dye-based BD-R media should be able to burn M-BD-R discs. I have not personally tested this, since I’ve been using burners specifically designed for M-Disc media since the beginning of the project — specifically, the LG series of multidrives for desktop personal computers.

Also, although the modern M-BD-R disc can hold 25 GB, this was not available in 2012. At that time, the largest M-Disk was a single-layer M-DVD, with only 4.3 GB available storage — problematic for storing feature-length films in high-resolution / high-profile digital formats.

Of course, it is also possible to use high-compression codecs to make feature-length films fit in this space, but there is a corresponding loss in picture quality, due to the lossy compression format.

Magnetic Media

Movies can also be distributed in even-higher profile format on magnetic media. “Digital Cinema Packages” are generally distributed on magnetic-media 3.5″ hard drives. Just like the ones in many desktop and server computers. This is not the most durable format, since magnetic media is also subject to fading over time, and the hard drive media are usually quite expensive per unit (these are the same hard drives you use in a typical desktop computer, and tend to cost around $50 – $100 each).

When you go to see a movie in a modern cineplex, you are likely watching a movie the theater received in this format. Although it is also possible that it was transmitted over the wire, with high-bandwidth internet. Both methods are in use today (2023).

These are usually in lossless formats: they store every pixel of the film accurately.

I don’t have a lot to say about this format. It’s not a very good option for consumers and collectors, but it does exist, and it gives me the chance to mention Digital Cinema Package (DCP) format, which I will come back to.

Flash Memory Media

Finally, there is another high-capacity digital storage format in wide consumer use today: flash media cards.

There are various physical form-factors for these, but the most popular are the “Secure Digital” (SD) cards, which come in several sub-formats, including the widely-popular “Micro SD” format, and the higher-capacity “XD” cards.

The main consumer market for these cards is as “digital film”. They are what you typically put in your camera.

In 2012, this seemed like a promising compromise among the available media, though they are not without faults.

Flash and magnetic media, both, are more prone to problems with storage: they need to be stored in a cool, dark, and dry environment (though not so dry that static electricity can build up). The same research study that tested optical media that I mentioned above also estimated the lifespan of flash memory modules at only about 10-12 years.

Flash media are also much smaller than optical disks, which seems like a benefit, but in fact, they are so small that accidentally losing them can be a problem!

Both magnetic and flash memory media can be rewritten, which is a possible solution for the fading problem: a diligent archivist could periodically rewrite their collection to new media, or even reuse the old media, writing new data to it, or refresh the old data by writing it back to the medium. But this does require the archivist to expend an ongoing effort to preserve the data!

Video Formats for Fixed Media

In addition to the physical storage of data bits, there is also the matter of how they should be organized. Furthermore, with the exception of the lossless Digital Cinema Package format, all the media considered here require the video data to undergo lossy compression to reduce them to a manageable size for writing to the data storage medium. A lossless copy of a high-definition feature length film tends to be a matter of a few hundred gigabytes of data: an amount that can be written to a conventional 3.5-inch hard drive, but not to the optical disc or flash media formats I’ve considered.

So compression algorithms are also essential to the success of digital fixed media for video.

For the DVD standard, the connection to broadcast and film media standards were also important. So, for example, video DVDs come in two major formats: NTSC, based on the 29.97 fps TV broadcast standard used in the USA and Japan, and PAL, based on the 25 fps standard used in Europe and Australia, with resolution corresponding to those broadcast standards.

Importantly, the analog broadcast signal standard specify the number of scan lines exactly, but not the number of pixels along each horizontal scan line. This is because the analog video signal varies continuously along the line. In establishing standard resolutions, the horizontal axis is broken down into a convenient number which comes close to the vertical resolution. However, it is not exactly the same, so that the pixels defined for standard television broadcast in NTSC and PAL formats are not “square”. This is a major difference from image standards designed for computers and computer monitors, which are generally defined to be exactly square for convenience of computing.

In addition to the non-square pixel aspect ratios, the entire television screen may be in more than one aspect ratio: for a long time, the 4:3 ratio reigned supreme in American households, but in the twenty-first century, the 16:9 “widescreen” format has become much more common. Almost all LCD flat panel television monitors sold today are in this aspect ratio.

DVD storage formats had to cope with this, and the most common method was the so-called “anamorphic DVD” format, in which the signal is simply assumed to be stretch to match the 16:9 format. This results in pixels that are substantially wider than they are tall, so the resulting image has noticeably higher vertical resolution than horizontal.

(next: high definition standards – 720p, 1080p, 2160p).

The main attraction of the DVD standard is that it is extremely well-established, to the point that most households in developed nations (and probably quite a few beyond that) have a player that can play them, even if they don’t have a desktop or notebook computer. They remain a fairly high-quality format for home-viewing, although their resolution falls short of what many common television monitors can display today.

They also have one particular problem for free-culture / free-software film producers like us: they are a proprietary format. This format has been pretty thoroughly (though perhaps absolutely completely) reverse-engineered.

This means that, although we do have good free-software tools for authoring DVDs that will play in virtually all DVD players, the resulting discs are not certified conformant with the DVD standard. As a matter of trademark law, it may be an infringement to use the official “DVD” trademark on them, even though the discs themselves are likely indistinguishable from discs made with approved proprietary authoring software. This is analogous to problems we have with “Adobe PDF” documents, where sites often advertise that you must have Adobe Acrobat installed to read them, even though, almost every PDF can be read by free-software tools like Evince.

Authoring DVD Movies

Nevertheless, it’s very clear that for our free-culture / free-software movie project, we are going to rely on the free-software authoring tools. There are essentially three tools of interest here, of which I have used two.

DVD-Author

First of all, it should be appreciated that there is a command-line based program that “compiles” DVDs from XML-based mastering files, which we could theoretically use directly. This is “dvdauthor”. Like FFMPEG, it is a bear to use on the command line, in practice, and writing the XML control files for it with only a text editor would be a very challenging job, requiring a lot of special knowledge of the format.

I have never attempted this, and so I’m not going to explain it. But you should know that it’s there, and the tools I am going to described operate by invoking it as their back-end.

Q-DVD-Author

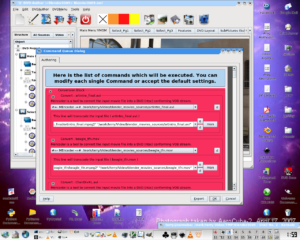

The first tool that I learned for making DVDs was Q-DVD-Author. This program should probably be regarded as obsolete at this point. It had some probably ill-advised user-interface color choices, which makes screen captures from the program extremely garish.

However, there are things I liked about this program a lot! The most important is that it was very transparent about what it was using on the back-end, so it would be an excellent starting point if you do want to end up editing your own XML files for dvdauthor. You could use Q-DVD-Author as a prototyping tool, and then tweak the files yourself, for example.

It facilitated that by showing you each of the tools it invoked, with the exact command line it would use, and also printed the output from the tool as it ran.

In this way, I’d say that Q-DVD-Author was, in spirit, like an Integrated Development Environment (IDE) — a tool intended for savvy developers who know what they’re doing, or at least, would like to. This does mean that it could be kind of scary to use, as it produced a lot of output along the way, just like watching a compiler run. This probably makes it a bit less than “user friendly”. But it was powerful.

Unfortunately, it’s also essentially unmaintained. It is still possible to find Q-DVD-Author in the KDE Store, but it has not been updated since 2009. A dedicated developer could no doubt bring it back from the demons of bitrot, but it is likely to become increasingly difficult to build as operating systems move on and it does not.

2010 FSM Article: Mastering a DVD using QDVDAuthor (or Archive)

There are not a lot of free software options for mastering DVDs. One of the more complete solutions is QDVDAuthor, although it still has a number of rough spots. It’s a front-end to a collection of command-line free software tools that do each of the individual steps involved in going from a collection of digital video files, audio files, and images to a DVD with menus. As such, it’s quite complicated, and not as stable as some software. Still, it is a rewarding experience if you stick with it.

2010 FSM Article: Making a videoloop with Kino and Audacity (or Archive)

In my recent article on QDVDAuthor, I skipped over the task of making a videoloop for the main DVD menu. Here I’m going to show you how I did it. The goal is a short loop of video that smoothly transitions through five different video segments and back to the beginning again.

In fact, I wound up moving to DVD Styler as a much more polished solution for DVD authoring. QDVDAuthor did have some pretty cool features, though, like the ability to follow in detail what was happening under the hood with the command line utilities it called to do the actual work.

DVD-Styler

However, I have not really found anything I wanted to do that Q-DVD-Author could do that I can’t also do with DVD-Styler, which is a much more end-user-friendly tool.

It does have a lot of end-user-directed features that I find slightly off-putting: templates to auto-generate DVD menus for people who don’t want to get creative with the design, and just want to put their home movies on disc. I do understand that this is probably a lot more users than the few of us who want to author complex DVDs with original movies and lots of “DVD Extras”.

But it is possible to create your DVD “from scratch” using DVD-Styler, which is what I’ve been doing for Lunatics Project, though we are not yet ready to release our first disc.

What About High-Definition Video?

The DVD standard makes no accommodation for high-resoution, high-profile video, which has become an expectation in the 21st century. The DVD “standard definition”, which is 720×480 pixels, seems hopelessly dated in 2025, and did already in 2012, although they are still generally watchable. So what comes next? The consumer video industry’s answer, after some flirtations with alternatives like “HD-DVD” and “China Blue”, has settled on “Blu-Ray”.

Neither of the aforementioned DVD authoring programs can master a Blu-Ray disc. For that, the options get very thin, probably because the Blu-Ray standard is complex, highly encumbered with “Digital Rights Management” (DRM), and licensed by bodies with a strong interest in restricting the production of Blu-Rays to those they approve.

Essentially, everything bad about the DVD standard — region coding, copying restrictions, arcane programming, non-free proprietary software — is far worse in the Blu-Ray standard.

I have been able to find a non-free, closed-source, but free-to-download program called “MultiAVCHD” which can make discs playable on most, if not all, consumer Blu-Ray players. And a commercial/proprietary program “Yuhan Blu-Ray Creator” which claims to produce true Blu-Ray discs. Neither program is available for Linux, and neither has source available. This situation does not seem to have changed in the last decade.

The other alternative is to give up on fixed-media and capitulate to the “online streaming video” culture, of total industry control at any given minute, over what you are allowed to watch.

What’s a free-licensed open-source software support, free-culture media enthusiast, and fixed-offline-media fan to do..?

2011 FSM Article: Five ideas for escaping the Blu-Ray blues (or Archive)

Some of us want to be able to release high-definition video (possibly even 3D) without evil copy protection schemes. I’ve been avoiding Blu-Ray as a consumer since it came out, mostly because Richard Stallman said it has an evil and oppressive DRM scheme. After my first serious investigation, I can confirm his opinion, and frankly, it’s a pretty bleak situation. What can we do about it? Here’s five ideas for how we might release high definition video.

Lib-Ray Project

In 2011, when I was first working seriously on Lunatics Project, the situation for fixed media was much as it is now, with the exception that the large-capacity BD-R compatible M-Disc media did not yet exist. It seemed to me that Digital Rights Management — the use of encryption technologies and secret keys to restrict the copying of discs — was not merely an undesirable feature of DVDs and Blu-Rays, but was actually their entire reason for being, and the main source of their complexity.

What’s more, the programmable menu systems for DVD and Blu-Ray were needlessly complex and esoteric, and were reinventing a wheel that HTML browsers had created many years earlier.

So I proposed making a simpler standard which would consist solely of:

- Videos formatted using an existing open-source and unencumbered video codec (originally Ogg Theora, but later VB8 or VB9).

- Menus which were essentially HTML or XHTML or a similar dialect of markup language.

- No programs to execute from the disc media, only passive, declarative language.

- Absolutely no DRM or other restrictions on playback or usage.

This would be a fixed media format expressly for use by free-culture / free-software film-makers, though anyone could technically use it. Given this was the target, it would also be desirable to meet some of the likely special requirements:

- Ease of use for one-off or short-run publication.

- Ease of updating with patches (such extra subtitles).

- Ease of import to digital library collections.

I went through a variety of names for the concept, but ultimately Karl Fogel suggested “Lib-Ray” (a pun on “Libre” and “Blu-Ray”, of course), and that’s what I’ve come to call it.

I originally figured that I would develop this as a part of Lunatics Project and ultimately release the series in this format in order to have a high-definition fixed-media release, without having to use the Blu-Ray format, which was antithetical to our values.

It seemed like this might be useful to more than just my project, though, and after succeeding with the first Kickstarter for Lunatics, I was considering whether this might be something to include in the budget for the larger Lunatics Production Kickstarter I was planning for Summer 2012.

Where I Went Wrong…

What happened next is one of my few real professional regrets. Thinking that Lunatics Project, as a creative story project, would have a broader appeal and be much more likely to succeed, I treated Lib-Ray as a kind of add-on, and decided to try to raise the funds for it first, to help me figure out the trajectory for the Lunatics Project.

I did not seriously consider the contingency of Lib-Ray succeeding at funding, but Lunatics Production failing. That is, however, exactly what happened. Even less did I consider the possibility that my wife would lose her job that year, throwing us into a deep financial crisis, and sending me into struggling for income.

Fortunately, of the $20,000 raised for Lib-Ray, $9000 was directly slated as income, and we were able to use some of that for survival. Unfortunately, I was pretty distracted by looking for more income, as that was certainly not sufficient for a family of five for very long. It was pretty tense.

Initially, the work went fairly well, though not quite as fast as I had hoped. I did a number of experiments with the file structure, mastering the data by directly using the back-end tools, and assembling HTML menus, which could be browsed with Chromium.

However, it was not so easy to integrate the video playback and menu elements, so I began working on a software to combine video playback with Gstreamer or LibVLC with menu-browser using WebKit. I got close to getting this to work, but a major problem I realized with WebKit is that it is an entire web browser, and is really not designed to be used strictly as a menu system.

This raises the specter of serious security vulnerabilities, since a malicious Lib-Ray volume might contain menus that directed the browser out to untrustworthy websites as part of some exploit. I would hate to wind up with a reputation like Microsoft Outlook for being a malware vector.

I was never able to resolve this problem, even after years of struggling with new architectures and trying to re-think the project. The Kickstarter has been a fiasco and a career faceplant I failed to deal with adequately, so that I’m still ashamed to talk about it. I was essentially completely blocked on solving this, for reasons which took some time for me to understand.

There is a whole side story here about me having personal revelations that I’m a neurodivergent personality who made it past 50 without being diagnosed, treated, or accommodated. This has resulted in career failures in the past, and this was yet another. I have since made considerable progress in that area, which may be a topic for another article.

However, not to get derailed, the important point here is that I went through multiple architecture concepts for the project. Now in 2025, I have a new, simpler concept, codenamed “Mitaka”, which I will spell out in a separate article.

2011 FSM Article: Assembling and Testing a Complex Ogg Theora Video with Command Line Tools and VideoLAN Client (VLC) (or Archive)

Unless you’ve been hiding in a cave for the last few years, you probably know about the free multimedia codecs with the fishy-sounding names from Xiph.org: Ogg Vorbis (for sound) and Ogg Theora (for video). You might be less familiar with other family and friends, including FLAC (lossless audio), Skeleton (metadata stream), and Kate (subtitles). However, together this collection of codecs can be used with the Ogg container format to provide all of the functionality of a DVD video file — multiple soundtracks, full surround sound, high definition, and selectable subtitles. Having created the various streams for a prototype release of “Sintel” in my last few columns, I’m now going to integrate them into a single video file and test it with some players.

2011 FSM Article: Assembling Ogg Soundtracks for an Ogg Video with Audacity, VLC, and Command Line Tools (or Archive)

Ogg Vorbis and Ogg FLAC (the Ogg stream version of the Free Lossless Audio Codec) are popular free-licensed and patent-free codecs for handling sound. These are the formats I’ll be using in a complex Ogg Theora video file that I am creating as part of my “Lib-Ray” experiment in creating an alternative format for distributing high definition video. In order to do this, I’ll need to solve several technical challenges using the FLAC command line tools, Audacity, and VLC, which I’ll demonstrate here.

2011 FSM Article: Assembling Video from a PNG Stream for an Ogg Video with png2theora (or Archive)

Ogg Theora is the codec of choice for free-licensed, patent-free video, and so that is the one I’ll be using in my experiment in creating an alternative format for distributing high definition video. The original, full-quality animation for “Sintel” is provided as a series of PNG images representing each frame, and so I’ll need to turn that into a high-quality Theora video stream for my prototype “Lib-Ray” version of “Sintel”. In this column, I’ll show how I do that.

2011 FSM Article: Creating Subtitles from SRT Sources for an Ogg Video with kateenc (or Archive)

One of the more interesting aspects of Ogg Video is that it allows an essentially unlimited number of subtitle tracks to be included. This is especially useful for free-culture videos, since they are generally released globally, and there are often contributed subtitles. In fact, for “Sintel”, I was able to find 44 subtitle files. I will be including them all as Ogg Kate streams in my prototype “Lib-Ray” version of “Sintel”, and in this column I will demonstrate the use of several command line utilities useful for this, especially the

kateenctool for creating the streams.

2011 FSM Article: Lasting Digital Archives: Millenniata’s New Archival DVD Technology (or Archive)

A new optical disk technology offers a fundamental new capability — which is storing offline archives in a format with a shelf life of many decades (or even centuries). The key is in the pits: unlike commonly available dye-based CD-R and DVD-R media, the Millenniata writer actually laser etches physical pits into the writable layer of its “M-Disc” DVD-ROMs. Because the pits are physical structures, like the pits on pressed media, they have the same kind of shelf-life — but in a way that is economical for low-copy archives. The niche here is for digital archives of “time capsule” data: family photographs, historical records, original manuscripts, video footage and masters, and so on. Perhaps more remarkably, the drives and disks, are affordable enough for the target applications and available commercially right now.

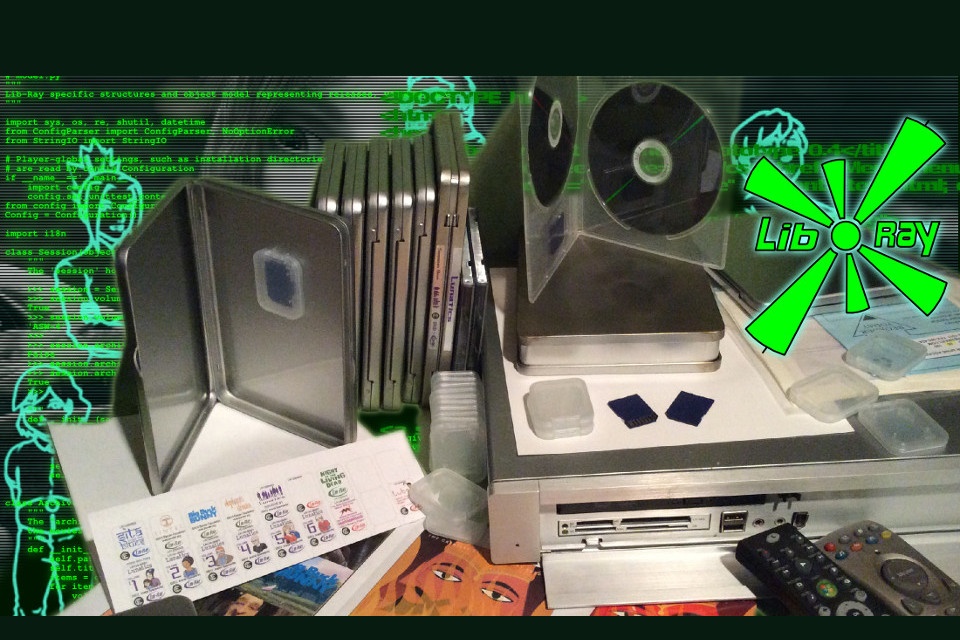

Disc Publishing in 2025: Bunsen Project Status

My progress on this front has been glacial, but I am still working on it. In 2022, I purchased a robotic disc duplicator machine, which is designed to burn discs individually and then print labels onto the discs (this requires discs with printable surfaces), for short production runs. At the time it was made, the M-Disc media did not exist, and it did not support Blu-Ray media.

Fortunately, the device simply contains a standard 5-1/4-in disc drive bay with a standard internal PC disc burner. And it exposes that disc device directly as a USB interface to the computer. That means that it can be replaced with any standard Disc burner. I determined this with my initial breakdown and analysis of the device, after I got it, confirming what I had guessed from the marketing materials.

2022 Production Log Article: Primera Bravo II – Breakdown

My first task is to do some reverse-engineering of my own. I have made some guesses about how this machine is engineered, but they’re only guesses, because I don’t have any design documentation. I also need to take the disk drive out of the machine in order to replace it with the upgraded drive.

2022 Production Log Article Primera Bravo II – Testing USB Topology

After disassembling the duplicator and removing the DVD burner, I needed to test how the data connections would work. The duplicator is a USB device, but how does it actually look to the computer? How does the DVD burner fit in? How does the signal get split between the DVD burner, the robot arm controls, and the printer?

Having established this, I later actually purchased an LG M-Disc DVD & Blu-Ray burner and installed it into the device.

2023 Production Log Article: Primera Bravo II – M-Disc Upgrade

To make sure the installation was working as expected, I connected the duplicator to power and to my workstation. I then mounted and read-back data from an M-BD-R disk to make sure the connectivity was working. Everything behaved as expected.

As that article mentions, the next step is to create a control program to operate the robotics in the device. With considerable research, I was able to find some information from people who had attempted to reverse-engineer the codes for this machine, but I have not yet tested them. I suspect that I will be able to do so, and the result will be a not-overly-complicated Python program, with functions to do basic high-level operations, like copy and print a single disc, or a stack of discs. Or to do copying or printing separately. And so on.

However, I have not yet made this attempt. My guess is that’ll be working on that in December or January, when it’s unpleasant outside.

One thing that does give me some anxiety about this machine is that it does take inkjet print cartridges, which have been fading into obsolescence for a long time now. I hope I will be able to keep finding supplies for the device and that the cartridges I can get will still work. This may require some considerable logistics and purchasing work (I assume that at some point I’ll have to get refurbished and/or rebuilt cartridges, and I’ll be at the mercy of there being a large enough market so that I can still find them.

Bunsen Architecture and Plans

I decided to call my disc-duplication control software “Bunsen”, because it’ll be based on the “Flask” Python web application library, which suggests a laboratory glassware theme. A “bunsen burner” is the classic laboratory heating solution, and the software is for “burning” discs. I wanted to use a web interface, so that I can connect the disc duplicator to a server in another room, but run the UI from my desktop workstation. With a client-server web architecture, I can do that anywhere. Since I also want to use this for backing up data off of the server onto archive discs, I will probably also incorporate some basic backup-system features.

But the development concept is as follows:

- Experimentally verify the control codes for the Primera Bravo II device.

- Encapsulate these with a suitable Python API, with allowance for other devices to be supported through plugin/driver modules.

- Integrate the special Linux printer driver used with the PB II (It’s based on a Lexmark printer), which exists, but I have not tested it.

- Write a simple command-line API for running the disc duplication process on the backend.

- Write a simple web-application front end, using the Flask library for Python.

- Install on our on-site server and attach it to the disc duplicator.

Other aspects of the disc publishing pipelines are simple, now:

- The duplicator has already been upgraded to handle Blu-Ray BD-R media, including M-Discs.

- M-Disc media come in 25-GB and larger sizes now.

- M-Disc single-layer DVD media are still available for short-run DVD releases.

- There are still DVD replication services for orders over 1000 units.

- DVD Styler is a standard part of my current AV Linux distribution, and I’ve recently tested it.

So the pieces are mostly in place, except for the software to burn and label the discs. Once completed, I believe I will have a complete Open Source, Linux-Based Disc Duplication work-flow for short-run M-Disc BD-R publication with integrated label-printing. I have not generally been able to find this offered as a service, so this may be quite rare, if not unique.

TO BE CONTINUED IN PART 5!

See also: